Augustine Against Gnosticism

Most American Christians are aware that it is an ancient heresy to say that Jesus was man but not God (Arianism); less are aware that there were just as many heretics who promoted the opposite error: that Jesus was God but not man (Gnosticism). The reason Gnostics denied that God became fully man in the incarnation is that they held a low view of matter in general and flesh in particular. For Gnostics, matter and flesh were not products of a good creation that fell; the creation of matter and flesh was itself the fall.

Although there are very few full-blown Gnostics in the church today, many Americans hold to a soft dualism that sees the soul as good and the body as bad. It is because of that theological misunderstanding that many Christians imagine that when we die, we become angels: that is, pure souls. Although Christians affirm in both the Apostles and Nicene Creeds their belief in the resurrection of the body, a suspicion of the flesh persists.

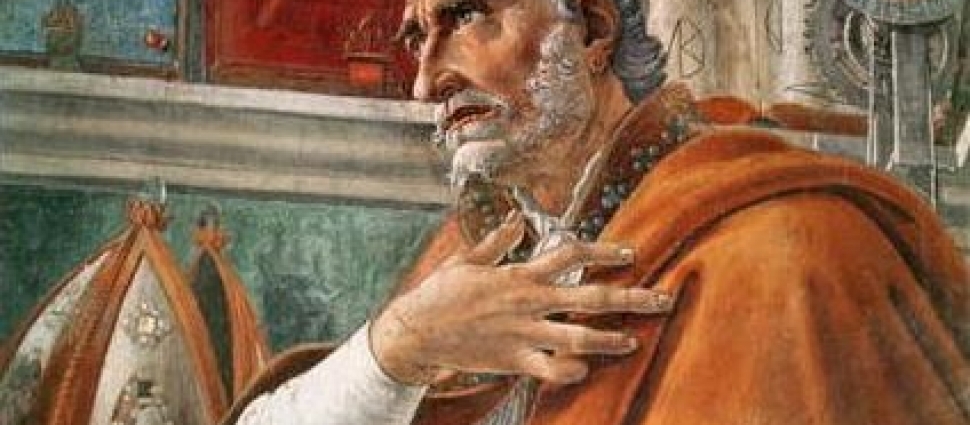

Thankfully, this gnostic, anti-biblical demonization of the flesh was dealt a decisive blow 1600 years ago in Book XIV, chapter 3 of The City of God. Although Virgil seemed to teach, in Aeneid 6, that the body weighs down the soul, Augustine insists that the Christian

faith teaches something very different. For the corruption of the body, which is a burden to the soul, is not the cause but the punishment of Adam’s first sin. Moreover, it was not the corruptible flesh that made the soul sinful; on the contrary, it was the sinful soul that made the flesh corruptible. Though some incitements to vice and vicious desires are attributable to the corruption of the flesh, nevertheless, we should not ascribe to the flesh all the evils of a wicked life. Else, we free the Devil from all such passions, since he has no flesh. It is true that the Devil cannot be said to be addicted to debauchery, drunkenness, or any others of the vices which pertain to bodily pleasure—much as he secretly prompts and provokes us to such sins—but he is most certainly filled with pride and envy. It is because these passions so possessed the Devil that he is doomed to eternal punishment in the prison of the gloomy air.

If flesh were the seat of evil, then none of the angels could have fallen. There are sins that rise up from the flesh, but they tend to be less wicked and corrupting than pride and envy, which rise up from the soul (see Mark 7:14-23). Indeed, it is more often the soul that leads the body astray than vice versa.

No, Augustine explains in chapter 4, “the animal man is not one thing and the carnal another, but both are one and the same, namely, man living according to man.” In fact, he continues in chapter 5, it is wrong “to blame our sins and defects on the nature of the flesh, for this is to disparage the Creator. The flesh, in its own kind and order, is good. But what is not good is to abandon the Goodness of the Creator in pursuit of some created good, whether by living deliberately according to the flesh, or according to the soul, or according to the entire man, which is made up of soul and flesh and which is the reason why either ‘soul’ alone or ‘flesh’ alone can mean a man.”

Those who are aware that St. Augustine played the central role in formulating the doctrine of original sin might be surprised to find Augustine here defending the body from its detractors. To be fair, Augustine, who went through a gnostic (Manichean) phase before embracing Christianity and whose pre-conversion years were marked by sexual promiscuity found it necessary to adopt a celibate lifestyle for himself and did sometimes speak in a disparaging manner of the flesh. Still, nowhere in his writings does he equate original sin with sex, nor does he treat the body as inherently fallen. Just as original sin tainted body and soul alike, so Christ’s atoning work on the cross restored body and soul alike.

Thus, in Book XIII, chapter 16 of The City of God, Augustine defends the vital Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the body against gnostic theologians who could not fathom why the soul, having been released from the flesh by death, would want to reunite with so corrupt and useless a thing as a body:

Some philosophers, against whose charges I am defending the City of God, that is to say, God’s Church, seem to think it right to laugh at our doctrine that the separation of the soul and body is a punishment for the soul, whose beatitude, they think, will be perfect only when it returns to God simple, solitary, and naked, as it were, stripped of every strength of its body…. [In fact,] it is not the body as such but only a corruptible body that is burdensome to the soul…. the soul is weighed down not by the body as such, but by the body such as it has become as a consequence of sin and its punishment.

For Augustine, as for orthodox church doctrine, man’s body and soul were equally created by God, equally fallen, and equally capable of restoration and glorification through Christ. We were created as incarnational beings (fully physical and fully spiritual), we continue to be so now, and it is our destiny to be so for eternity. Yes, between our death and the second coming of Christ, there will be a period when our body and soul will be separated, but our final destiny it to be clothed forever in a glorified resurrection body like that of Christ himself (see Romans 8:11,18-23, 1 Corinthians 15:35-57, 2 Corinthians 5:1-10, Philippians 3:20-21).

Although the teaching that we are enfleshed souls and that our incarnational nature shall persist after death is a uniquely biblical one, Augustine, in City of God XIII.16, argues that there are glimmerings of it in Plato’s Timaeus: “Plato teaches that the gods are mortal by virtue of their union of body and soul, and immortal by the will and decree of the God who made them…. the supreme God had granted to the lesser gods, whom he had made, the favor of never dying, in the sense of never being separated from the bodies which he had united to them.” One may also find a foreshadowing of our amphibian nature in Aristotle’s philosophical, rather than theological, concept of hylomorphism (see On the Soul II.1).

#

For the sake of pure doctrine and proper theology, we desperately need to be reminded of Augustine’s teachings on these matters. And yet, more than doctrine and theology are at risk. Many of our current social ills spring directly from our misunderstandings of the incarnational relationship between our souls and our bodies.

Although the Gnostics of the early church identified the sinful body with the female of the species—reasoning that it is she who tempts men to lust, ties them to an earthly, physical existence, and, worst of all, produces more evil flesh in her womb—the American dualists of today identify the body with the male. Whether we realize it or not, Americans tend to look with greater disfavor on more masculine, body-based sins like violence, drunkenness, substance abuse, sexual promiscuity, and general crudeness than on more feminine, soul-based sins like gossip, vanity, hypocrisy, envy, and resentment.

In grammar schools across the country, this same dualism manifests itself in an overly-feminized classroom that insists on trimming back the natural physicality of male students—even to the point of putting boys on unnecessary drugs that interfere with their developing brains and brand them unfairly as bad or at least difficult students. We are incarnational beings, not disembodied brains, and educators must take account of our physical/spiritual amphibian nature. What has been called the “war on boys” is not just a manifestation of radical feminism; it is deeply undergirded by a dualistic mindset that mistrusts the body and sees it as a hindrance to intellectual and spiritual growth.

Our bodies are not arbitrary clothing to be mistreated by rough handling or contemptuous neglect. The various gnostic groups of the early church, like the ones that lured in the young Augustine, were notorious for adopting both extremes: now indulging in orgies; now subjecting their bodies to unhealthy asceticism and the forbidding of marriage. It is most likely America’s deeply ingrained dualism that accounts for the disturbing seesawing in our country between morbid obesity and a worship of severe exercise that borders on idolatry. Certainly, the rise in excessive tattooing and piercing, not to mention cutting, betrays a dis-ease with the body in modern America.

Most recently, the western world’s gnostic separation of the human person into a good soul and a bad body has manifested itself in the postmodern transgender movement. This radical, ultimately anti-humanistic form of dualism drives an arbitrary wedge between a person’s physical, biological sex and their so-called gender. To honor their “true” or “authentic” internal sense of gender, no matter how nebulous or confused it may be, many people today, an alarming number of them children, will hire surgeons to mutilate their body so as to bring it into conformity with their “soul.”

One of the earliest gnostic groups were known as Docetists, from a Greek verb that means “to seem.” They called themselves that because they believed that Jesus did not actually take on human flesh but only appeared to do so. Many today believe the same thing about our own bodies, that they are useful coverings but have no ultimate connection to who we “really” are. Sadly, such dualistic reasoning does not set us free from the “tyranny” of the body; it only deconstructs what makes us uniquely human.

Let us take up Augustine’s City of God and read it again lest we slip further into a gnostic nightmare world where soul (person/gender) and body are torn asunder.

Louis Markos, Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Christian University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities; his 25 books include From Plato to Christ, The Myth Made Fact, Atheism on Trial, and Ancient Voices: An Insider’s Look at the Early Church. His Passing the Torch: An Apology for Classical Christian Education and From Aristotle to Christ are due out in 2024 and 2025.