Chapter 29.3, 4

July 31, 2013

iii. The Lord Jesus hath, in his ordinance, appointed His ministers to declare His word of institution to the people; to pray, and bless the elements of bread and wine, and thereby to set them apart from a common to an holy use; and to take and break bread, to take the cup and (they communicating also themselves) to give both to the communicants; but to none who are not then present in the congregation.

iv. Private masses, or receiving this sacrament by a priest, or any other, alone, as likewise, the denial of the cup to the people, worshipping the elements, the lifting them up, or carrying them about, for adoration, and the reserving them for any pretended religious use; are all contrary to the nature of this sacrament, and to the institution of Christ.

Celebrating the Supper

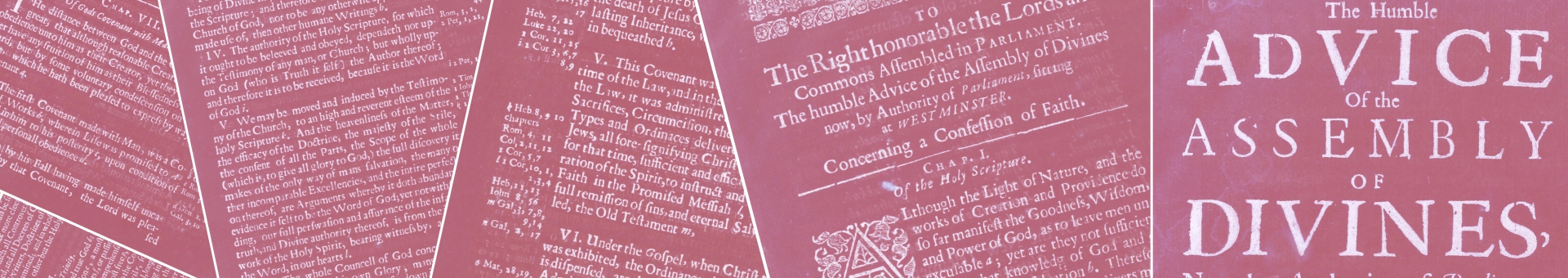

Having defined the essence of the supper in paragraphs one and two, the Confession directs the celebration of the supper in paragraphs three and four. The place to find basic directives on the celebrating of the supper is in the fourfold summary of the first supper recorded in the first, second, and third gospels and in one epistle (Matt. 26:26-28; Mark 14:22-24; Luke 22:19-20; 1 Cor. 11:23-26). There we find three key features.

First, Jesus, serving as the prime minister of the new covenant, declared his word of institution - he directed his disciples, telling them what to do and when, and explaining what the elements and actions meant. His disciples then passed this instruction on to other disciples, although the subject of the supper is important enough that the Apostle Paul appears to have received instructions on the supper directly from the risen Christ himself.

Second, we can see from these four accounts that as an essential ingredient of the supper we are to mix in prayer, as we see Jesus himself doing. These prayers are to include a petition for the blessing of the elements, asking God to set apart what is common to be used for a purpose that is holy. We are to ask that God would take this ordinary bread, and ordinary wine, and bless it by his Holy Spirit for extraordinary good.

Third, the minister is 'to take and break' the bread, and 'to take the cup' and, not forgetting to partake of the meal themselves, they are to give the supper to all those who are communing with Christ and his people at that supper, as Christ did on the night when he was betrayed.

Private Communion

The last line of the third paragraph specifies that the Lord's supper is not to be received privately. One reason why the Westminster assembly frowned on bringing the bread and wine to persons not present in the worship service, was presented in paragraph one: this meal is intended to celebrate communion with Christ, but also with fellow Christians.

A second related reason why the Westminster assembly disapproved of private communion is found in the Bible itself: not only did the individualistic approach of the Corinthians earn an apostolic rebuke (1 Cor. 11:20; c.f., 17-22), it seems to have been the settled pattern of the first Christians to 'gather together to break bread' rather than to eat in isolation (e.g., Acts 20:7).

A third reason why the assembly worked to banish the still-popular practice of private communion is suggested in paragraph two and clarified in the opening line of paragraph four: Roman Catholics had long inflated the saving efficacy of the mass and offered private masses as a kind of life-line to grace. The assembly considered the continuation of private communion a poor example, even in churches where the theology of the Lord's supper had been corrected. Like the Israelites who were to remember the rebels of the wilderness days, Protestants were to remember the Romanists of the theological wilderness and avoid their ways (1 Cor. 10:6).

Pretended Religion

Having forbidden private communion, the assembly tackled other ceremonial abuses too. The most egregious was the Roman Catholic practice of forbidding people to drink of the cup, lest they accidentally spill the blood of Christ on the floor of the church. Suffice it to say that when Jesus gave the cup, he gave it to all disciples, both the coordinated and the clumsy (Mark 14:23; 1 Cor. 11:25-29). The practice of withholding the cup from the laity was a gradual, natural, and tragic development from the idea that the wine miraculously become blood when blessed by the priest - a theory which the assembly confronts in paragraphs five and six.

Actually, any additional ceremonies attached to the supper and required either of those who administer or of those who receive the supper is an offence to God. Bowing down to the elements, lifting up the elements, parading the elements, adoring the elements, storing them for later religious purposes - all of these activities oppose the true nature of the sacrament and subvert the simple institution of Christ. It is vain worship - empty and useless. Yet all of these practices were commanded by the Roman Catholic church, with penalties for nonconformity. Some of these practices were commanded by the Church of England, with penalties for nonconformity. Both the Reformation and post-Reformation histories vividly illustrate the drift and the danger to leaders in the church who 'teach as doctrines the commandments of men' (Matt. 15:9).

Dr. Chad B. Van Dixhoorn is Professor of Church History at Reformed Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. and associate pastor of Grace Orthodox Presbyterian Church in Vienna, Virginia. This article is taken from his forthcoming commentary on the Confession, published by the Banner of Truth Trust.