Chapter 7.1, Part Two

February 26, 2013

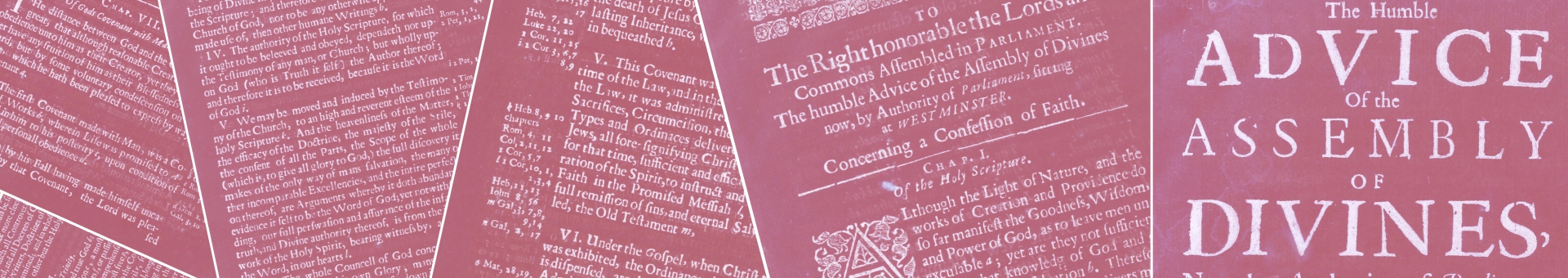

i. The distance between God and the creature is so great, that although reasonable creatures do owe obedience unto Him as their Creator, yet they could never have any fruition of Him as their blessedness and reward, but by some voluntary condescension on God's part, which He hath been pleased to express by way of covenant.

Point 2. It is worth noting, as we saw yesterday, and it is a master-stroke of theological genius, that the Confession begins its section on covenant, as it must, with the majestic and incomprehensible character of God. This must be the starting place for all thinking about God and his relationship to creation. Any theology that goes wrong in its assessment of God inevitably goes wrong because it begins its theologizing with "God-in-relationship" rather than with the a se and immutable Triune God. One might have thought that since the Confession already affirmed these things about God in chapter two, there would be no need to introduce such things again. But the genius of this chapter is that it was recognized that unless the "distance" between God and his creatures is first affirmed, any notion of covenant would be anemic, because it would be tied to a dependent God. This, of course, has proven to be the case in a vast swath of past and current theology.

Once we recognize the ontological "distance" between God and creatures, which includes the fact, as section one says, that even though we owe obedience to him, we could have no "fruition of him as our blessedness and reward," we are then in a position to affirm just what it is that brought about God's relationship to his creatures.

Two monumentally pregnant words - "voluntary condescension" - serve to affirm the initiation of God's relationship to His creatures, and we need to focus on each of them. What does the Confession mean by "voluntary" with respect to God? In theology proper (which is the doctrine of God), we make a distinction between God's necessary knowledge/will and His free knowledge/will. This distinction is not tangential to our understanding of God; it is crucial to a proper grasp of His incomprehensible character. It is natural to affirm that God's knowledge and will are necessary. As One who cannot but exist, and who is independent, we recognize that God knows all things, just by virtue of who He is, and whatever He wills with respect to Himself is, like Him, necessary. Why, then, do we need to confess that God's knowledge and will are, with respect to some things, free?

We confess this, in part, because the contrary is impossible, given who God is. Since He is independent and in need of nothing, there was no necessity that He create anything at all. If creation were necessary, then God would be dependent on it in order to be who He is. But, pace Barth and his followers, there is no such dependence in God. So, God's determination to create, and to relate Himself to that creation, is a free decision. Two things are important to keep in mind about God's free knowledge and will.

First, the free knowledge and will of God have their focus in what God determines. That which God determines is surely something that he knows (for how could God determine that which was unknown; and what, in God, could be unknown?). That which God knows and determines is that which he carries out. In other words, to put it simply, there is no free knowledge of God that is not also a free determination, or will, of God. The two are inextricably linked.

God's knowledge is a directing knowledge; it has an object in view. His will enjoins (some of) that which he knows, and his power executes that which his will enjoins. When discussing God's free will, therefore, what he freely knows just is what he freely wills. We can see now that with the notion of "voluntary condescension" we have moved from a discussion of God's essential nature, that is His ontological distance, to an affirmation of his free determination to create, and to condescend. This is something that God did not have to do; so, we move from a discussion of God's essential nature, to a discussion of his free activity.

Secondly, the free will of God is tied to his eternal decree. This is important for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it reminds us that God's free will does not simply and only coincide with his activity of creation, but is itself eternal. His free will includes the activity in and through creation, but is not limited to that activity. God's free determination is an activity of the Triune God, even before the foundation of the world.

Point 2. It is worth noting, as we saw yesterday, and it is a master-stroke of theological genius, that the Confession begins its section on covenant, as it must, with the majestic and incomprehensible character of God. This must be the starting place for all thinking about God and his relationship to creation. Any theology that goes wrong in its assessment of God inevitably goes wrong because it begins its theologizing with "God-in-relationship" rather than with the a se and immutable Triune God. One might have thought that since the Confession already affirmed these things about God in chapter two, there would be no need to introduce such things again. But the genius of this chapter is that it was recognized that unless the "distance" between God and his creatures is first affirmed, any notion of covenant would be anemic, because it would be tied to a dependent God. This, of course, has proven to be the case in a vast swath of past and current theology.

Once we recognize the ontological "distance" between God and creatures, which includes the fact, as section one says, that even though we owe obedience to him, we could have no "fruition of him as our blessedness and reward," we are then in a position to affirm just what it is that brought about God's relationship to his creatures.

Two monumentally pregnant words - "voluntary condescension" - serve to affirm the initiation of God's relationship to His creatures, and we need to focus on each of them. What does the Confession mean by "voluntary" with respect to God? In theology proper (which is the doctrine of God), we make a distinction between God's necessary knowledge/will and His free knowledge/will. This distinction is not tangential to our understanding of God; it is crucial to a proper grasp of His incomprehensible character. It is natural to affirm that God's knowledge and will are necessary. As One who cannot but exist, and who is independent, we recognize that God knows all things, just by virtue of who He is, and whatever He wills with respect to Himself is, like Him, necessary. Why, then, do we need to confess that God's knowledge and will are, with respect to some things, free?

We confess this, in part, because the contrary is impossible, given who God is. Since He is independent and in need of nothing, there was no necessity that He create anything at all. If creation were necessary, then God would be dependent on it in order to be who He is. But, pace Barth and his followers, there is no such dependence in God. So, God's determination to create, and to relate Himself to that creation, is a free decision. Two things are important to keep in mind about God's free knowledge and will.

First, the free knowledge and will of God have their focus in what God determines. That which God determines is surely something that he knows (for how could God determine that which was unknown; and what, in God, could be unknown?). That which God knows and determines is that which he carries out. In other words, to put it simply, there is no free knowledge of God that is not also a free determination, or will, of God. The two are inextricably linked.

God's knowledge is a directing knowledge; it has an object in view. His will enjoins (some of) that which he knows, and his power executes that which his will enjoins. When discussing God's free will, therefore, what he freely knows just is what he freely wills. We can see now that with the notion of "voluntary condescension" we have moved from a discussion of God's essential nature, that is His ontological distance, to an affirmation of his free determination to create, and to condescend. This is something that God did not have to do; so, we move from a discussion of God's essential nature, to a discussion of his free activity.

Secondly, the free will of God is tied to his eternal decree. This is important for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it reminds us that God's free will does not simply and only coincide with his activity of creation, but is itself eternal. His free will includes the activity in and through creation, but is not limited to that activity. God's free determination is an activity of the Triune God, even before the foundation of the world.