Opposite but the Same

October 13, 2014

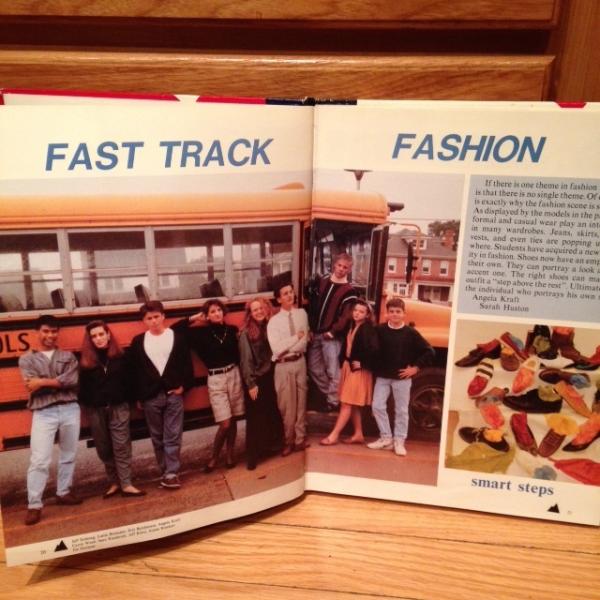

I remember the time. I remember it well. This girl was selected for the fashion page in my first year of high school. Yep, picture in the yearbook. That’s me in the mustard skirt, representing the girls in the Freshman class.

This is a reputation I took seriously. I didn’t want to be like all the others--- you know, those who wore what the mannequins in the store were displaying in the window. No, I needed to be ahead of the mannequins. And the poseurs. Cutting edge. Look at me.

And yet I still fell for the same, old shtick as the others. In high school, I wouldn’t be caught dead in a second hand store. But in college, it was revolutionary. Embracing the poverty of student living, I enjoyed the hunt through second hand clothing, and treasured a good find, as well as the admirers of my one-of-a-kind steal. I was cutting edge cool. But my best piece was a jacket that my grandma saved from my dad’s middle school years. I claimed it for my own and was stopped by strangers asking where they could buy it all the time. “Oh this thing? Sorry, this was my dad’s back in the day. Can’t find it anywhere now” (smiling inside because you’re not as cool as me).

Until about ten years later, when I was way past that stage. You know, I was now shopping Banana Republic Outlet. That’s when I realized that some of my younger acquaintances were thinking they were cutting edge by (wait for it…) second hand shopping. They looked just like I did ten (okay, maybe 15) years ago. Who did they think they were? They weren’t cool; they were mere imitators. The college look. They thought they were being different, but they were the same. (But for the record, my dad’s coats are still cool, and I’ve acquired a collection of his and my grandpa’s. Total score.)

Why am I sharing all this on a website that is supposed to be about theology? Well, there are certainly parallels. And I ran into one while reading Todd Brenneman’s Homespun Gospel. Brenneman’s comparison of Max Lucado and Rob Bell in his chapter, “You are Special,” is spot on. The subtitle is A Tale of Two Hells. Both Bell and Lucado use sentimental means to promote their popular message. They endorse themselves as the cool ones---the ones in the know. The author notes that although you would think that the doctrine of hell is not one that would be discussed in “evangelical sentimentality,” this is where these two seemingly different theologians are the same.

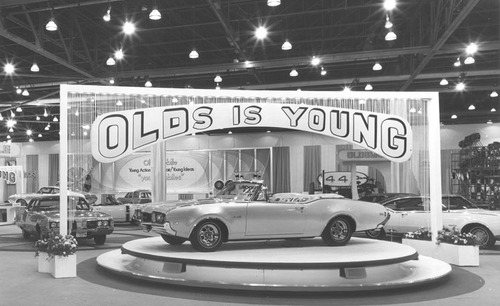

And Bell would want to separate himself from Lucado. I mean, just look at Bell. He’s hip. And although he may look like he’s wearing his father’s old jacket, he is emphatically not driving his father’s Oldsmobile, theologically speaking. Not like Max Lucado. Sure, I haven’t read Max Lucado, but his very name is associated in my head with a Thomas Kinkade picture. Dreamy. Not raw. Not authentic.

And Bell would want to separate himself from Lucado. I mean, just look at Bell. He’s hip. And although he may look like he’s wearing his father’s old jacket, he is emphatically not driving his father’s Oldsmobile, theologically speaking. Not like Max Lucado. Sure, I haven’t read Max Lucado, but his very name is associated in my head with a Thomas Kinkade picture. Dreamy. Not raw. Not authentic. Oh, but he is the same. They are the same. And you are not special either.

On the surface, they seem to be opposite, I’m sure much to Bell’s delight and intent. Lucado affirms the existence of an eternal hell and a just God. But, like Bell, the two popular writers and speakers give hell a sentimental treatment. While affirming its existence, Brenneman demonstrates that Lucado downplays hell by “elevating” individualism. He insists that a loving God would never send people to hell; we volunteer for that lot: “He conceals this fearful language under the saccharine sentiment of God’s love” (76).

And Bell, well, despite his academic schooling, he masters “postmodern sensibilities” to try and enlighten us that Jesus never taught about an eternal hell. Without spelling it out (I-am-wearing-my-dad’s-coat), Bell expressed an evangelical cool that didn’t need to affirm eternal hell (Oldsmobiles).

Brenneman is insightful enough to recognize that:

Bell’s postmodern proclivity toward polyvocality, however, also begins to evidence how much in common Bell has with Lucado and others. Polyvocality is another way to think about the downplaying of doctrinal differences. The route to arrive at this position might take a different direction, but it arrives at a very similar destination. (78)

The author emphasizes that these two men start at the same place: God’s love. While Lucado tries to remain traditional and Bell tries to look divergent, they both reduce hell to something that we can choose now and has sentimental implications in the future. It all emphasizes the familial bonds of fatherhood that appeals to our nostalgic sense of family.

Ironically, Bell believes that even though he doesn’t drive his father’s Oldsmobile, we will all soften “and even the most ‘depraved sinners’ will eventually give up their resistance and turn to God’” (79). And Lucado affirms the existence of hell on the convoluted basis of God’s love for our special selves. It is a love that will even allow for us to make the rare decision to go there, absent from that very love. Love, love, love. “All we need is Love.”

Brenneman concludes, “It remains to be seen whether the vision of the sentimental moderns or the sentimental postmoderns will shape the next generation of evangelicals. What does seem clear, however, is that even postmodern evangelicals believe in the authority of the emotional, often at the expense of the intellectual.” (80)

Maybe they all just look like college. They think they are being insightful. They think they are opposite of their ancestors in enlightening us. But really, they all look the same.