Reading Reflection:

December 26, 2011

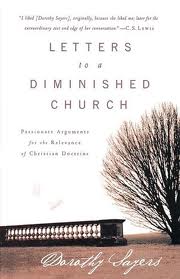

Letters to a Diminished Church, Dorothy Sayers (Thomas Nelson,2004)

What a great book. The subtitle, Passionate Arguments for the Relevance of Christian Dogma, would not be very popular for today’s Christian culture; but I would love to see this book make a comeback. For example, what do our Christian beliefs have to do with the goods we produce? What kind of work does a Christian do? Well, one of the essays is a speech she gave at Eastborne, England in 1942 called, Why Work? The thing I like about Sayers is that she asks the “right” questions that we sometimes don’t recognize are staring us right in the face. Here’s an example from Why Work?

Letters to a Diminished Church, Dorothy Sayers (Thomas Nelson,2004)

What a great book. The subtitle, Passionate Arguments for the Relevance of Christian Dogma, would not be very popular for today’s Christian culture; but I would love to see this book make a comeback. For example, what do our Christian beliefs have to do with the goods we produce? What kind of work does a Christian do? Well, one of the essays is a speech she gave at Eastborne, England in 1942 called, Why Work? The thing I like about Sayers is that she asks the “right” questions that we sometimes don’t recognize are staring us right in the face. Here’s an example from Why Work?

The habit of thinking about work as something one does to make money is so ingrained in us that we can scarcely imagine what a revolutionary change it would be to think about it in terms of the work done. To do so would mean taking the attitude of mind we reserve for unpaid work—our hobbies, our leisure interests, the things we make and do for pleasure—and making that the standard of all our judgments about things and people. We should ask of an enterprise, not “will it pay?” but “is it good?”; of a man, not “what does he make?” but “what is his work worth?”; of goods, not “can we induce people to buy them?” but “are they useful things well made?”; of employment, not “how much a week?” but “will it exercise my faculties to the utmost?” And shareholders in—let us say—brewing companies, would astonish the directorate by arising at shareholder’s meetings and demanding to know, not merely where the profits go or what dividends are to be paid, not even merely whether the workers’ wages are sufficient and the conditions of labor satisfactory, but loudly, and with a proper sense of personal responsibility: “What goes into the beer?” (132-133).This sounds like something so obvious, yet maybe of which we have just lost complete sight. We look at work as a means to an end. A living. A lifestyle. A status even. Sayers argues, “work is not a thing one does to live, but the thing one lives to do. It is, or it should be, the full expression of the worker’s faculties, the thing in which he finds spiritual, mental, and bodily satisfaction, and the medium in which he offers himself to God” (134-135). In our attempts to be more spiritual, we have confused the idea of spiritual work. We think that it is only a moral issue, or even a Christianizing issue. So, in order to feel like we are living for God, we have Christian contractors and Christian soccer for our children. But we neglect the thought of the work itself. Sayers laments:

In nothing has the Church so lost Her hold on reality as in Her failure to understand and respect the secular vocation… The Church’s approach to an intelligent carpenter is usually confined to exhorting him not to be drunk and disorderly in his leisurely hours, and to come to church on Sundays. What the Church should be telling him is this: that the very first demand that his religion makes upon him is that he should make good tables… No piety in the worker will compensate for work that is not true to itself; for any work that is untrue to its own technique is a living lie (138-139).True-to-the-that! One of my biggest pet peeves is shoddy, second-class work being passed off as the so-called Christian version. Like I said, this seems so obvious, but so revolutionary. I want to give everyone a copy of this essay as our new mission statement for the American work force! What if our candidates for the Presidency actually addressed the quality of the work over the amount of jobs? How would welfare reform if our focus were on the beauty of good work?