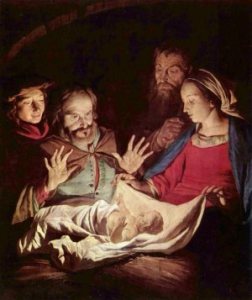

Jesus in the Flesh (1)

March 3, 2009

“The Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.”

- John 1:14

The first chapter of John’s Gospel is the clearest statement of what the early church Fathers sometimes called the en-manning of the Savior. More commonly we call this the incarnation of Christ which literally means His en-fleshment. Over the next few posts I want to tease out a bit the implications of Christ being made flesh and dwelling among us.

First, we must know where to begin with Jesus. That is, do we begin with his humanity or his divinity? I suggest, contra many liberal theologians, that the incarnation requires that our consideration of Christ must begin with His divinity. Indeed, the incarnation pre-supposes that Christ’s nature is both eternal and divine. His existence did not begin in the womb of the virgin. “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

Looking to Jesus’ divine nature as our starting point is often times referred to as a Christology “from above.” Liberal theologians would have us embrace a Christology “from below.” That is, they separate the “Jesus of faith” from the “Jesus of history.” Their presupposition is that the real Jesus was not Divine, did not perform miracles, and was not bodily resurrected. He was simply a good man whose followers later projected upon him their own hopes and dreams. Some of these liberal theologians would say this should not present a barrier to faith. Indeed, they say, what is important is not so much historical facts but the inner experience of faith. Thus, one’s faith need not falter even if the Jesus of history and the Jesus of faith are completely different personages.

The New Testament, however, is univocal in presenting a Christology from above. Only after establishing the eternal and divine nature of Christ are we told that Jesus became a man. In John 1:1 we are told that “the Word was God.” He did not become God. He was not adopted by God. Jesus has been from eternity very God of very God. In contrast John tells us that “the Word became flesh” (v. 14). “Became” is in the aorist tense which is punctiliar, meaning that the Word became flesh at a particular moment in time. The Word was always divine but He became flesh in one specific moment.

In the next posts we will consider the humanity of Jesus’ body, mind, and emotions. Along the way we will consider whether or not Jesus’ humanity involved his erring or making mistakes.

- John 1:14

The first chapter of John’s Gospel is the clearest statement of what the early church Fathers sometimes called the en-manning of the Savior. More commonly we call this the incarnation of Christ which literally means His en-fleshment. Over the next few posts I want to tease out a bit the implications of Christ being made flesh and dwelling among us.

First, we must know where to begin with Jesus. That is, do we begin with his humanity or his divinity? I suggest, contra many liberal theologians, that the incarnation requires that our consideration of Christ must begin with His divinity. Indeed, the incarnation pre-supposes that Christ’s nature is both eternal and divine. His existence did not begin in the womb of the virgin. “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

Looking to Jesus’ divine nature as our starting point is often times referred to as a Christology “from above.” Liberal theologians would have us embrace a Christology “from below.” That is, they separate the “Jesus of faith” from the “Jesus of history.” Their presupposition is that the real Jesus was not Divine, did not perform miracles, and was not bodily resurrected. He was simply a good man whose followers later projected upon him their own hopes and dreams. Some of these liberal theologians would say this should not present a barrier to faith. Indeed, they say, what is important is not so much historical facts but the inner experience of faith. Thus, one’s faith need not falter even if the Jesus of history and the Jesus of faith are completely different personages.

The New Testament, however, is univocal in presenting a Christology from above. Only after establishing the eternal and divine nature of Christ are we told that Jesus became a man. In John 1:1 we are told that “the Word was God.” He did not become God. He was not adopted by God. Jesus has been from eternity very God of very God. In contrast John tells us that “the Word became flesh” (v. 14). “Became” is in the aorist tense which is punctiliar, meaning that the Word became flesh at a particular moment in time. The Word was always divine but He became flesh in one specific moment.

In the next posts we will consider the humanity of Jesus’ body, mind, and emotions. Along the way we will consider whether or not Jesus’ humanity involved his erring or making mistakes.