Chapter 31

August 14, 2013

i. For the better government, and further edification of the church, there ought to be such assemblies as are commonly called synods or councils; and it belongeth to the overseers and other rulers of the particular churches, by virtue of their office, and the power which Christ hath given them for edification and not for destruction, to appoint such assemblies; and to convene in them, as often as they shall judge it expedient for the good of the church.(1)

ii. It belongeth to synods and councils, ministerially to determine controversies of faith, and cases of conscience; to set down rules and directions for the better ordering of the public worship of God, and government of his church; to receive complaints in cases of maladministration, and authoritatively to determine the same: which decrees and determinations, if consonant to the Word of God, are to be received with reverence and submission; not only for their agreement with the Word, but also for the power whereby they are made, as being an ordinance of God appointed thereunto in his Word.

iii. All synods or councils, since the Apostles' times, whether general or particular, may err; and many have erred. Therefore they are not to be made the rule of faith, or practice; but to be used as a help in both.

iv. Synods and councils are to handle, or conclude nothing, but that which is ecclesiastical: and are not to intermeddle with civil affairs which concern the commonwealth, unless by way of humble petition in cases extraordinary; or by way of advice, for satisfaction of conscience, if they be thereunto required by the civil magistrate.

Does the doctrine of the church really matter? Isn't it of far less importance than the gospel, personal piety, or mission? So what if your congregation is independent, congregationalist, presbyterian, or episcopalian? What difference does it make? Our confession is that God's Word provides answers to these questions.

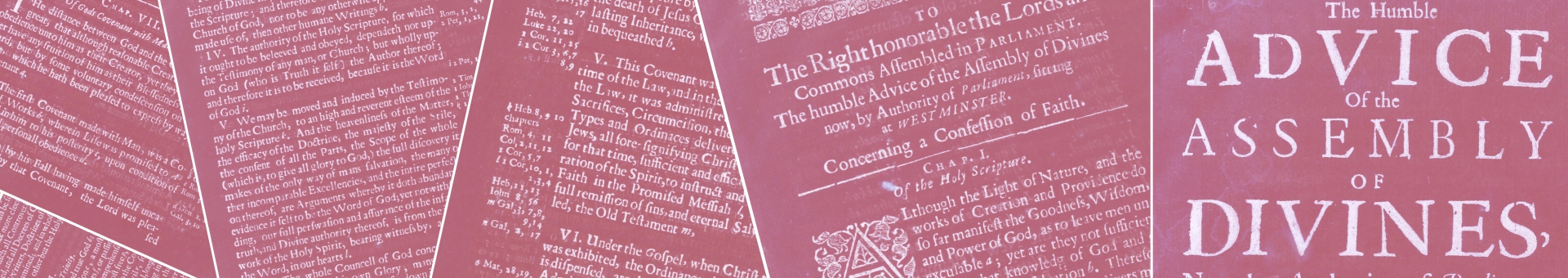

When it is faithfully lived in coherence with the Word of God, the doctrine of the church is not some dry, arcane, or at best third-tier thing. It is a living testimony of the fruit of the Spirit, a living witness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. It brings glory, honor, and delight to him, just as much as showing mercy to orphans or singing his praises does. The scripturally revealed doctrine of the church is Christ's mandate for the shape and function of the kingdom of heaven in its earthly manifestation. Chapter 31 of the Westminster Confession of Faith, building on previous chapters (cf. 25, 30), summarizes the teaching of Christ by his Word on the church, in this case focusing particularly on "synods and councils".

Synods and councils are scripturally warranted (cf. Acts 6:2-3; 11:27-30; 15:2-6, 23-25; 21:15-25) and should be called to meet together by teaching and ruling elders of local church bodies, "as often as they judge it expedient for the good of the church". The book of Acts testifies to this pattern with regular occurrences of gatherings of the apostles, ministers, and elders to deliberate on and address issues of importance for both local congregations and the broader church as a whole. Local church bodies are to be connected with others in a meaningful mutual accountability, particularly through (and including) their ministers and elders. Our confession notes that this is a part of the delegated and derivative authority, the "power" given by Christ to the overseers of the church, "by virtue of their office".

The Confession next addresses the nature and extent of the work engaged in by synods and councils. Following the paradigm of the book of Acts, the role of synods and councils is (1) "to determine controversies of faith, and cases of conscience", (2) "to set down rules and directions for the better ordering of the public worship of God, and government of his church", (3) "to receive complaints of maladministration, and authoritatively determine the same." Following Scripture's pattern, we are to maintain a high view of these actions and decisions of synods and councils when their actions and decisions are consistent with God's Word. Our confession is that "they are to be received with reverence and submission; not only for their agreement with the Word, but also for the power whereby they are made, as being an ordinance of God appointed thereunto in his Word." Like Paul in his challenge to an erring Peter (Galatians 2:14), in love for Christ, his church, and fellow overseers, we are called to make use of the means God has given in ordaining synods and councils in dealing with needs and problems in the life of the church.

Section three of this chapter reminds us that synods and councils do not possess infallibility. They "may err, and many have erred." Our confession reminded us in the previous section that the Word of God is the rule of life and practice; it now reaffirms this by reminding us that synods and councils "are not to be made the rule of life and practice". They are "to be used as a help in both" life and practice of the church and her members (2 Corinthians 1:24), but remain subordinate to the Word of God (1 Corinthians 2:5).

Taking hold of these concepts does great good in promoting the prosperity of the church in peace, unity, and truth in Christ. Is there an unresolved problem in your local congregation despite all attempts to resolve it locally with the church session or consistory? Bring it by appeal to the broader and higher courts (presbytery, synod, and/or assembly) of the church, seeking resolution according to and in harmony with God's Word. Do you find that you disagree with part of the church's confession on scriptural grounds? Bring it to the higher court of the church--the presbytery. Do so prayerfully looking to God and His Word, and honoring the means the ascended Christ, the head and governor of the church, has given to address the issue. If outstanding disagreement remains and you cannot submit in good conscience before God to what you believe is an erring court, then appeal to a yet broader and higher court--the synod or assembly. By scriptural paradigm (cf. Gal. 2:14; Acts 15), the Confession indicates that broadest and highest court of the church, in its entirety, ought to be the place of final appeal; where denominations have judiciary committees or commissions at the synod or assembly level, these committees and commissions ought to report in a manner open to review and reconsideration by, and requiring the ratification of, the entire body of the synod or council. If you believe that a synod or council of final appeal errs in its deliberation and determination, and you are convicted you cannot acquiesce or remain in fellowship, then tell them, and prayerfully determine together with them (if possible) what to do.

The final section further addresses the limitation of the scope of the work of synods and councils: "they are to handle, or conclude nothing, but that which is ecclesiastical: and are not to intermeddle with civil affairs which concern the commonwealth." (Luke 12:13-14; John 18:36) The responsibility of synods and councils is restricted to issues of the life of the church: controversies of faith; cases of conscience; public worship; church government; and complaints of maladministration of these. At its broadest definition this includes the ecclesiastical church as an entire body, with its courts, particular congregations, and their agencies of ministry. Synods and councils are only to make comment on "civil affairs which concern the commonwealth" in "extraordinary cases", and then by "humble petition" to the secular government. They are to provide advice and counsel to the magistrate when required or requested to do so.

Our confession provides great wisdom as it summarizes Scripture's teaching, given by Christ to and for his church. We confess that the doctrine of the church, including her form and function of government, matters. It matters because Christ has displayed in his Word how the church is to be shaped and governed for her good and His glory.

Dr. William VanDoodewaard is an ordained minister in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, and serves as Associate Professor of Church History at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary.

NOTES:

1. This version of the Westminster Confession of Faith, chapter 31, is that which is held by the Presbyterian Church in America and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. It is an American modification of the original chapter, rewording the role given to the civil magistrate in the calling of synods and councils in response to concerns in the late 1700's that the original version allowed for interference by the civil magistrate in the life of the church. The Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church's version of the Westminster Confession of Faith retains a closer form to the original, though its revision also narrows the potential role of the civil magistrate in calling synods and councils to "extraordinary cases" in which it is "the duty of the church to comply." This is further qualified by an annotation on the relationship of church and state, noting that the church "does not accept the principle of ecclesiastical subordination to the civil authority, nor does it accept the principle of ecclesiastical authority over the State." The Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America maintains the original wording of the Westminster Confession of Faith but amends its meaning through its Declaration and Testimony, with results similar to the revisions of the PCA, OPC, and ARP. To see an explanation of the original version consult David Dickson, Truth's Victory over Error: A Commentary on the Westminster Confession of Faith (Banner of Truth, 2007), 253-254.