Chapter 1.1

January 14, 2013

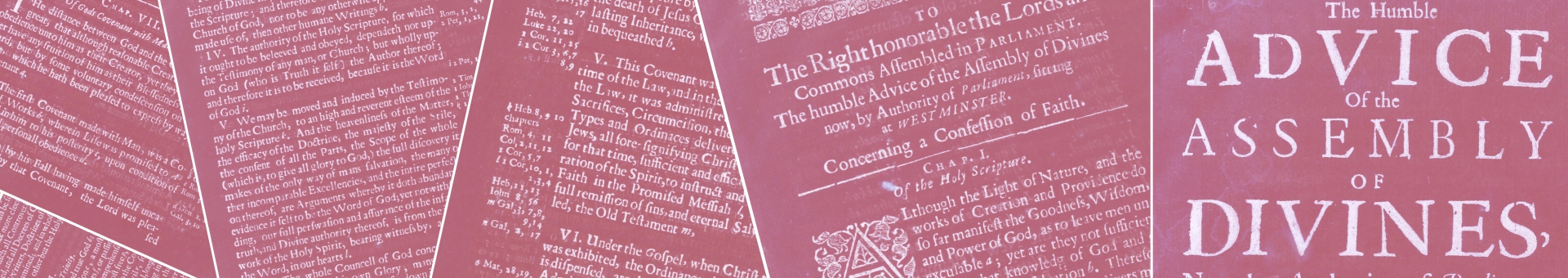

i. Although the light of nature, and the works of creation and providence do so far manifest the goodness, wisdom, and power of God, as to leave men inexcusable; yet are they not sufficient to give that knowledge of God, and of His will, which is necessary unto salvation: therefore it pleased the Lord, at sundry times, and in divers manners, to reveal Himself, and to declare that His will unto His Church; and afterwards, for the better preserving and propagating of the truth, and for the more sure establishment and comfort of the Church against the corruption of the flesh, and the malice of Satan and of the world, to commit the same wholly unto writing; which maketh the Holy Scripture to be most necessary; those former ways of God's revealing His will unto His people being now ceased.

This first paragraph of the Confession makes it clear that Scripture is necessary if there is going to be a knowledge of salvation. The confession says that "it pleased the Lord." It does not state that it was necessary for God to reveal what He did; He decided to reveal that of His own good pleasure, or His own mercy.

For the framers of the Westminster Confession, Scripture is foundationally and essentially divine. It is worth noting that in WCF I, there is no mention of the human authors of Scripture. This is not an oversight in the Confession; it is not that the Reformers and their progeny did not recognize the human element of Scripture. It is not that they were not privy to extra-biblical sources and other cultural, contextual and human elements. Rather, it is in keeping with the testimony of Scripture itself about itself that the WCF affirms that Scripture is foundationally and essentially divine (though contingently, secondarily and truly human).

For the Reformed, God is the author of Scripture, and men were the ministers, used by God, to write God's words down. Scripture's author is God, who uses "actuaries" or "tabularies" to write His words. Reformed thought has been careful to see God as the primary author, and men as instrumental, secondary authors.

This means that a doctrine of Scripture can only be constructed by way of what Scripture itself says about itself. We do not build a doctrine of Scripture by looking at the surrounding culture and intimating what Scripture is, based on that culture. To do that will involve us in hopeless confusion. We won't know, for example, how to compare certain creation narratives of a surrounding culture with the creation account given to us by God in Scripture. All narratives, including those in Scripture, become nothing but "literature."

While it is appropriate and important to seek to understand biblical passages in terms of their cultural context, it is inappropriate, in a Reformed, confessional context, to let those phenomena determine what the Bible is (i.e., a doctrine of Scripture). Such a methodology denies that we determine our doctrine of Scripture in terms of its self-witness alone. To let our understanding of the "cultural context" of the Bible determine its meaning denies that a doctrine of Scripture is gleaned, first of all, by virtue of what Scripture says about itself.