The Struggle in the City

Roman Catholics and Protestants alike often appeal to the massive body of works penned by Augustine, Bishop of Hippo. The thinking behind the Reformation was seeded by the ad fontes principle of the Renaissance, and for theologians those sources were often the Church Fathers, particularly Augustine. For example, the Battles edition of Institutes of the Christian Religion by John Calvin includes an extensive list of citations to Augustine in its index. Likewise, Luther was an Augustinian who often made use of his order’s namesake’s works in his writings. Thus, Bishop Augustine of Hippo enjoys the status of being the church father of Roman Catholicism and the church father of Protestantism, though the theologians of each often appeal to Augustine for different reasons.

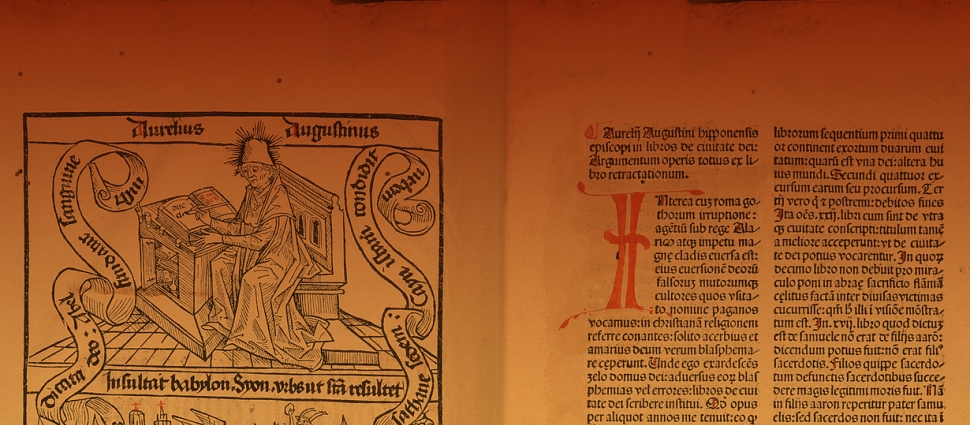

Augustine is most famously known for two of his works—Confessions and The City of God (De Civitate Dei). The massive City of God traces the history of two cities, that of man and that of God. Augustine wrote the book for an apologetic purpose, responding to the accusation that Christians are atheists because they do not worship the gods, and that this failure to worship the deities caused the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in AD 410. On the contrary, Augustine pointed out that it was God’s grace that spared both Christians and pagans from death. It was the accepted practice of the art of war to kill all the inhabitants of a captured city, but the Visigoths did not follow the accepted practice of the day (1:1,2,5). Because of God’s providential restraint of the Visigoths for the preservation of the Christians and their churches, many non-Christian Romans were also spared. Augustine adds that the Romans were foolish for trusting gods who were incapable of defending them (1:3), and the disciples of the true God put the followers of the false gods to shame when Christians provided refuge for Rome’s citizens in church facilities (1:7).

The blessings and misfortunes which fall on the “good” and the “evil” are viewed differently—the “good” see their loss of property as something insignificant (1:10), while the “evil” are disheartened by their losses. Other issues relevant to the war are discussed including suffering (1:15), rape (1:16,18,19), and burying bodies (1:12,13). Augustine observes that fallen Rome was still a vice-ridden city, as exemplified by theater attendance (1:32), but he contends that God spared the pagan Romans so they could repent and enter the city of God (1:34). The Bishop concludes that on earth the two cities are somewhat mixed: “In truth, these two cities are entangled together in this world, and intermixed until the last judgment effect their separation” (1:35).

As such, there is a tension between what the city of God presently enjoys and what it will ultimately become. The city of man is that abode of those fallen in sin, separated from God. It is of the earth, insensitive to the heavenly. The city of God is inhabited by those who live their lives at rest in God, pursuing righteousness and putting aside the temptations and lusts of the flesh.

Augustine looks to Abraham and his two sons to describe the antithesis between the two cities. Isaac was born of the free woman, of the promise, and through the covenant from Jerusalem, while Ishmael was born of the bond woman, of the flesh, and through the covenant from Sinai (15:2). Citizens of the heavenly city are begotten “by grace freeing nature from sin,” “begotten by promise,” and “are vessels of mercy,” but residents of the city of man are born to it “by nature vitiated by sin” and are “vessels of wrath” (15:2). The antithesis is described further as Augustine discussed Cain and Abel:

…it is recorded of Cain that he built a city, but Abel, being a sojourner, built none. For the city of the saints is above, although here below it begets citizens, in whom it sojourns till the time of its reign arrives, when it shall gather together all in the day of the resurrection; and then shall the promised kingdom be given to them, in which they shall reign with their Prince, the King of the ages, time without end (15:1).

The city of God is populated by, “those who live according to God,” but the antithetical city of man is inhabited by, “those who live according to man” (15:1). As an apologist and rhetorician, Augustine repeatedly makes the point that these are two distinct cities. Never the twain shall meet, unless one moves from the city of man to the city of God through grace.

Augustine sees an eschatological tension between the ultimate fulfillment of the heavenly city at the end of time and the present residence of its citizens on earth: “It is thus, the citizens of the city of God are healed while still they sojourn in this earth and sigh for the peace of their heavenly country” (15:6). Life on this earth as a citizen of the divine city is difficult, though blessed, but the eschatological fulfillment of the civitatae Dei is the object of the Christian’s yearning.

Book nineteen deals particularly with philosophy and the vanity of its speculations, showing “how the empty dreams of the philosophers differ from the hope which God gives to us” (19:1). Augustine presents an analysis of Marcus Varo’s De Philosophia and concludes that Varo sees the purpose of philosophy to be achieving happiness, and that the “supreme good” is “that which makes him happy” (19:1). After further discussion of Varo, Augustine concludes that life eternal is the supreme good, and death eternal is the supreme evil (19:4). Ultimate happiness is through the city of God and eschatological citizenship in heaven, “the unending end” (19:10). Man seeks happiness in many ways, but most of all he seeks peace—even warriors, who seek peace by pursuing happiness through victory (19:12). The earthly city seeks an earthly peace, but the heavenly city enjoys earthly peace as a taste of eternal peace (19:17).

Book twenty goes on to present the Bible’s teaching on the last judgment and God’s work as judge. God, says Augustine, is always judging, but there is the unique judgement that he will make on the last day (20:1). The good suffer and the evil prosper in this life (20:2). Life is vain if it is pursued in unbelief, but the certainty of the future judgment helps the good to keep a proper perspective (20:3). The remainder of the book is dedicated to a presentation of the final judgment, the resurrection of the dead (20:6,10), the meaning of the millennium (20:7-9), the devil’s end (20:14), the glory of the church (20:17), and expositions of several texts from the Old and New Testaments relevant to the final judgment (20:18-30).

The City of God is a massive exposition of the antithesis between good and evil, righteousness and unrighteousness, the heavenly and the earthly, and the material and immaterial. Augustine’s philosophical journey through the dualism of Neoplatonism and Manichaeism left residue on his presuppositional foundation, which he was able partially to remove as he increased in his knowledge of the Word of God. As one reads the works of Augustine, moving from the earlier to the latter treatises, one finds that Augustine was able to renew his mind through the Scriptures and progressively divest himself of much of the dualism... but not all.

Augustine’s struggles, particularly with sexual promiscuity, were to affect his thinking throughout his life and contribute to his teaching regarding monasticism and celibacy. Even though Augustine struggled to make his thoughts captive to the Word of God (as his protégé Luther would say at Worms) the residue of dualism influenced him to view his body and the material world with suspicion. The material distracts the pious from their pursuit of sanctification and feeds temptation. But as Martin Luther experienced, the removal of the material through monkery could not eliminate the sin from within. In The City of God, Augustine does not describe the material and the body as evil, but the way he expresses the differences between the city of man and that of God might lead one to conclude the material, bodily, and earthly are of questionable value.

Scripture teaches that there is the spiritual which is unseen, and there are those things which constitute the tangible creation, but the flesh, creation, body, and the material are not necessarily evil; they are good, though affected by sin (Ps 8:1, 19:1-6, 24:1; 1 Tim 4:4), and they shall enjoy eschatological redemption (Rom 8:19-21). Augustine would likely affirm the goodness of the physical and material, but the overall tenor of City betrays lingering dualism.

- - - - - - -

Sources—The City of God, translated by Marcus Dods, in The Modern Library series, Random House, 1950; Augustine Through the Ages: An Encyclopedia, edited by Allan D. Fitzgerald, OSA, Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1999; Mary Clark, Augustine, in the Outstanding Christian Thinker Series, edited by Brian Davies OP, London, 1994, 1996. The lovely pages of De Civitate Dei are from copies on Internet Archive.

Notes—Regarding Augustine’s dualism, Mary Clark, Augustine, p. 105 says, “As a mature thinker Augustine was influenced more by Scripture than by the Manichees and Neoplatonists.” I have adopted her assessment in my article even though I think Augustine had more difficulty shedding the idea that the material was evil than Clark does. Regarding Augustine’s monastic views see Marriage and Concupiscence, for instance, where he affirms that marriage is holy too, but asceticism and celibacy are even better. The City of God was written between 413 and 427

Barry Waugh (PhD, WTS) is the editor of Presbyterians of the Past. He has written for various periodicals, such as the Westminster Theological Journal and The Confessional Presbyterian. He has also contributed to Gary L. W. Johnson’s, B. B. Warfield: Essays on His Life and Thought (2007) and edited Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I (2012).

Related Links

"The Quest for Rest in Augustine's Confessions" by Barry Waugh

"Reading Augustine with Collin Garbarino" by Carl Trueman

PCRT '95: Two Cities, Two Loves [ Audio Disc | MP3 Disc | Download ]

Augustine Of Hippo - Christian Biographies For Young Readers by Simonetta Carr

Entering God's Rest by Ken Golden [ Paperback | eBook ]

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on Presbyterians of the Past (August 2017)