Singing with the Saints

For decades now, Christian congregations have had to deal with differences in musical styles in Christian worship. Some prefer "contemporary music." Others prefer "traditional music." The differences become a source of contention. Sadly, we now have the term "worship wars," as a label to describe the extent to which music in worship has become a battleground.

We should not want more wars, especially within the bounds of the church. Therefore, a discussion of music and singing in the church must begin by recalling Christ’s command: Christians should love one another as Christ has loved us (John 15:12 ESV; see 13:34; 1 John 4:19). Loving one another is a central principle in the life of the people of God. We need not only to teach the principle, but to practice it. Any disagreement or tension in the body of Christ should be seen as an occasion to practice Christian love.

My purpose here is not to talk about Christian love, important as that is. My focus is rather on one specific element: congregational singing. I wish not to create tension, but to ask both pastors and musicians, both leaders and followers in the Christian faith, to approach the issue of congregational singing with wisdom and with balance. For the sake of the health of the church, we want congregational singing to contribute to that health.

How do we best do that? In this four-part series, I briefly set forth my own thoughts. Even if other brothers and sisters may not agree, I hope this may help lead the conversation in a positive direction.

As we have observed, one prime factor is love, and with love, patience. We should bear with other people in the congregation, and bear with decisions about singing with which we disagree. But now what else should go into the decision-making and practice of a Christian congregation?

Mind the Goal

What should be the long-range goal in congregational singing? Everything that we do in Christian worship and in all of life, we should do for sake of honoring God, that is, for sake of promoting the glory of God: "So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God" (1 Cor. 10:31). The glory of God is primary and essential.

In addition, the Bible indicates that church meetings should have the aim of building up the church: "Let all things [that take place when the people assemble] be done for building up" (1 Cor. 14:26). The goal is that the people should grow in spiritual maturity, not only individually but as a body, as a community. Nearly the whole of 1 Cor. 14 is about the importance of building up the church, and how this goal regulates and guides the details of what happens during a congregational assembly. Likewise Eph. 4:1-16 has a focus on building up the church. According to Eph. 4, the goal is "the stature of the fullness of Christ" (verse 13). We are "to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ" (verse 15).

We have two goals before us: the glory of God and the building up of the church. These two goals are not two diverse goals that pull in opposite directions. Rather, each implies the other. Building up the church takes place properly only when we are serving God and seeking to please him. So we need to seek the glory of God in Christian worship.

We can also reason the other way, starting with the glory of God. Seeking God's glory includes seeking to honor his commandment to love one another. This means we cannot seek God's glory properly without attending to the goal of building up the church. Seeking the glory of God and seeking to build up the church are two sides of the same coin. The two aspects, oriented toward God and toward fellow Christians, are intended by God to work together harmoniously.

How do we build up the church? Much is involved. We need the power of the Holy Spirit, who dwells in us and among us. We need wisdom. In the points that follow, I want to give thoughtful input to pastors, leaders, and musicians who must work with skill and wisdom in many situations, in many congregations, with a variety of needs.

For the People, by the People

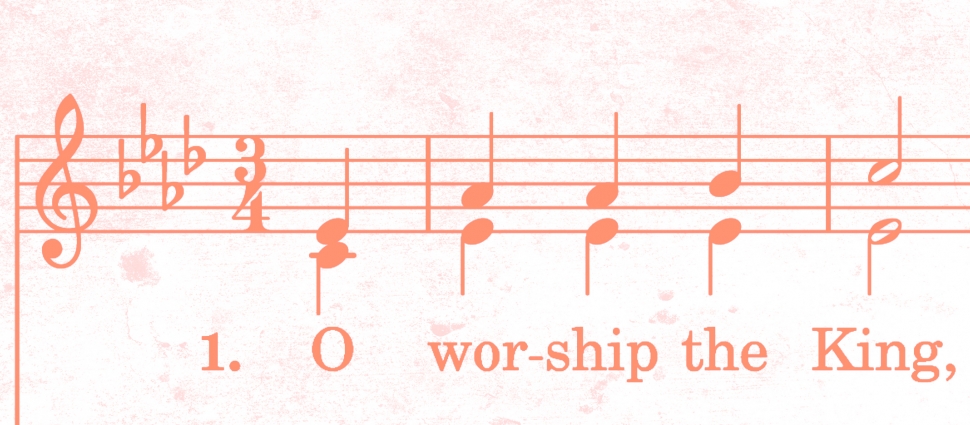

First, let us consider the role of the congregation in singing, in distinction from soloists and choirs. The Old Testament gives evidence that some singing in worship was done by trained choirs of Levites (1 Chron. 16:7; 25:1-31; Ezra 3:10-11). But the common people also sang (Ps. 137:3-4; see also 30:4; 67:4; 68:32; 96:1). The apostles sang "a hymn" just before they went out after the Last Supper (Matt. 26:30). Through the Apostle Paul, God instructs early Christians to sing:

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. (Col. 3:16)

According to Col. 3:16, singing is in effect a form of "teaching and admonishing one another." The teaching takes place not only by hearing the message that people around us sing, but by singing the message ourselves. This benefit is confirmed by modern observations about how people learn. People learn more effectively and more deeply if they not only hear, but try to re-express what they learn. Getting one's voice involved deepens one's participation. Singing engages our emotions, and may help to make the message more memorable. People remember songs that they have sung repeatedly, and embrace them more deeply. Their active participation reinforces their memory.

Performance, or Participation?

It follows that there should be a place in Christian worship for the whole congregation to sing, not only for choirs or soloists or musicians. The whole congregation will typically include many people with little or no training in music, and little formal training in the specific skills of singing. The musical quality will not be at the same level as the quality of trained choirs and trained soloists.

We must not be embarrassed by this participation of ordinary people. God is pleased with it, and not embarrassed. It follows also that trained musicians may sometimes need to make mental and emotional adjustments. They must not despise what they hear just because it is not the heightened quality of the highly trained person. In other contexts, perhaps, they would prefer to hear and perform only music of the highest aesthetic quality, with greatest skill and elegance in performance. But that preference has to be set aside in Christian worship. Building up the congregation takes precedence. That does not imply that no attention should be given to musical quality. But the quality must serve the main goal. Other things being equal, higher quality music, with high quality musicians, is going to serve more effectively to build up the church. But other things are not always equal!

Everyone must be ready to resist the pressure towards top quality music if it comes at the expense of the congregation and the need for building up. Even people with no special musical training can sometimes intuitively sense the superiority in the performance of a choir or a soloist. They themselves may find that they prefer it to their own participation. But we need to resist the idea that Christian worship is primarily the place for a performance. Performance is for concert halls and YouTube channels; Christian worship is for building up. And for that purpose, we should seek not entertainment, but participation. The participation can at times be more passive, as when people are listening to a sermon. But even here, they need to engage mentally, emotionally, thoughtfully. For a sermon, some people find that they do better when they take notes.

Is there any room for a soloist or a choir or a musical piece without words? Many churches will have music while the offering is being collected. People need to pay attention as they look for the offering plate, writing out a check or pulling out some money in the process. Their minds cannot be fully focused on singing a song, so that is a good time to do something special. And because it is done by people with some training, one may hope that it will be of higher musical quality as well. Many church services also include a "prelude" and a "postlude," instrumental musical pieces immediately before and after the service. Churches may schedule a Christmas concert, where the focus is much more on the music, and Christians may easily invite their non-Christian friends to come.

Granting the above, I suggest that our singing should be predominantly congregational, rather than by specialists or instrumental performances. Why? Because of the need for building up through active speaking (Col. 3:16).

Welcomed to Church

What about outsiders who come to a Christian meeting? They should be welcome. We glorify God not only by building up the people who are already Christian believers, but by adding to the church people who are new, people who have just begun to believe in Christ. Unbelievers are welcome to come to church because they can hear the invitation to come to Christ. God may bring them to faith.

But then we may raise the question: "Should a Christian meeting be oriented primarily to guests, not to church members?" Certainly there may be evangelistic rallies where the primary purpose is to welcome and address unbelievers. But should the regular Sunday meetings of the church have that primary purpose? That is controversial.

We cannot fully respond to that issue here. The New Testament shows that the assemblies for worship have a focus on God and on the body of Christ, not primarily on unbelievers who may be present (1 Cor. 12; Eph. 4:1-16; but note also 14:23-25). Unbelievers themselves need to see Christians for who we are what we are like as a group—not merely what we put on for display to outsiders.

Congregational singing, like other elements of worship, fits into this picture. Primarily, it should serve God and Christian believers, not outsiders.

Meetings for worship should be conducted for the glory of God, and for the purpose of building up the people, the Christian community. Building on the above principles, we begin to sketch the distinct features of congregational singing over against performances. But that we will save for another time.

Vern S. Poythress is Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Biblical Interpretation, and Systematic Theology at Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he has taught for 45 years.

Related Links

Podcast: "What Happens When We Worship"

"A Shallow View of Singing" by Josh Irby

"A Hymn That Would Not Be Written Today" by Gabriel Fluhrer

Pleasing God in Our Worship by Robert Godfrey

What Happens When We Worship by Jonathan Landry Cruse