For All The Saints

Editor’s Note: This post has been adapted from a longer article set to be published in a forthcoming edition of the Puritan Reformed Journal.

For most professing Christians in modern North America, Cyprian's dictum—“No one can have God for his Father, who does not have the Church for his mother”— may seem strange, if not downright offensive. Yet as we saw in our last post, theologians of the Reformation and Post-Reformation eras agreed with Cyprian on the corporate nature of Christianity.

The Belgic Confession and Heidelberg Catechism both insist, in no uncertain terms, that individual believers must be involved in the corporate life of God’s people. Ultimately, there are no "solo Christians"; the primary means of spiritual growth and communion with God are found through participation in communion with the saints.

But these documents were by no means abnormal. In fact, the substance of the Belgic Confession can likewise be seen in Second Helvetic Confession (1566) Composed in 1566 by Heinrich Bullinger not long after the Belgic Confession, the Second Helvetic (Swiss) Confession is not a mirror copy of the Belgic. Nevertheless, it shares the previous confession’s insistence (and perhaps even boldness of tone) on the individual Christian believer’s involvement in the corporate life of God’s people. In chapter 17, entitled “Of the Catholic and Holy Church of God, and of The One Only Head of the Church,” the confessions states:

WHAT IS THE CHURCH? The Church is an assembly of the faithful called or gathered out of the world; a communion, I say, of all saints, namely, of those who truly know and rightly worship and serve the true God in Christ the Savior, by the Word and holy Spirit, and who by faith are partakers of all benefits which are freely offered through Christ.[1]

And further in the same chapter (emphasis mine in italics):

OUTSIDE THE CHURCH OF GOD THERE IS NO SALVATION. But we esteem fellowship with the true Church of Christ so highly that we deny that those can live before God who do not stand in fellowship with the true Church of God, but separate themselves from it. For as there was no salvation outside Noah's ark when the world perished in flood; so we believe that there is no certain salvation outside Christ, who offers himself to be enjoyed by the elect in the Church; and hence we teach that those who wish to live ought not to be separated from the true Church of Christ.[2]

Note how the Confession emphasizes the church’s character of a gathered (or corporate) people given to a corporate identity and therefore corporate activities (such as worship in order to facilitate the preaching of the Word, baptism, and the Lord’s Supper). Note also the repeated mantra (first from Cyprian, made famous by Calvin) that there is no hope of salvation for an individual outside of the church of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Later in chapter 22, the Second Helvetic Confession, while never denying the important role of individual practices of piety, again insists on the primacy of the church’s corporate functions (emphasis mine in italics):

WHAT OUGHT TO BE DONE IN MEETINGS FOR WORSHIP. Although it is permitted all men to read the Holy Scriptures privately at home, and by instruction to edify one another in the true religion, yet in order that the Word of God may be properly preached to the people, and prayers and supplication publicly made, also that the sacraments may be rightly administered, and that collections may be made for the poor and to pay the cost of all the Church's expenses, and in order to maintain social intercourse, it is most necessary that religious or Church gatherings be held. For it is certain that in the apostolic and primitive Church, there were such assemblies frequented by all the godly.

MEETINGS FOR WORSHIP NOT TO BE NEGLECTED. As many as spurn such meetings and stay away from them, despise true religion, and are to be urged by the pastors and godly magistrates to abstain from stubbornly absenting themselves from sacred assemblies.[3]

Leaving the Continental Reformed tradition for a moment, we can make brief mention of the Scots Confession of 1560 composed by John Knox and several other leading Scottish ministers. While an earlier confession which does not elaborate on the doctrine of the church or the communion of saints at length the way some later confessions do, nevertheless, the seeds of these later doctrinal flowerings are still evident in the Scots. In chapter 16, (Of the Kirk) the Confession states (emphasis mine in italics):

[The] kirk: that is to say, a company and multitude of men chosen of God, who rightly worship and embrace him, by true faith in Christ Jesus…which kirk is Catholic that is, universal…who have communion and society with God the Father, and with his Son Christ Jesus, through the sanctification of his Holy Spirit; and therefore it is called the communion, not of profane persons, but of saints, who…have the fruition of the most inestimable benefits: to wit, of one God, one Lord Jesus, one faith, and of one baptism; out of the which kirk there is neither life, nor eternal felicity.[4]

Note how this Confession emphasizes the church’s catholic or universal character and also her communal nature—a people who commune one with another and also with the Triune God. This confession assumes an insistence on the church’s gathered worship and corporate nature, albeit the language is not as forthright as some of its sister confessions. Nevertheless, the implicit insistence is there as evidenced by the fact that it speaks of the Kirk in chapter 16 and proceeds to speak of the sacraments, their right administration and the rightful recipients in chapters 21-23—sacramental activities which are essential to Christian discipleship and only properly experienced in a corporate setting and facilitated amongst the gathered people. Additionally, like the Second Helvetic and Belgic Confessions, the Scots Confession also invokes that popular confessional mantra with slightly altered language, declaring that outside the church “there is neither life, nor eternal felicity.”

As one will observe repeatedly in our brief survey of these Reformation and Post-Reformation era documents, these confessions assume a communal and corporate participation of the Christian life, made clear if by no other reason than the attention given to the sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper as two of the primary means of grace and spiritual nurture—sacraments which by definition are administered within the context of the assembled, corporate church.[5]

Certainly not to be overlooked, we must take note of the Westminster Confession of Faith’s emphasis on the church and the communion of saints. As the Second Helvetic Confession, Heidelberg Catechism, and Belgic Confession bore great impact on the theological distinctives and ecclesiastical life of the Reformed churches on the Continent, so too Westminster bears such impact on both Scottish and later English Presbyterian traditions. In chapter 25 of the Confession, Westminster states (emphasis mine in italics):

2. The visible church, which is also catholic or universal under the gospel (not confined to one nation, as before under the law), consists of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion; and of their children: and is the kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ, the house and family of God, out of which there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.

3. Unto this catholic visible church Christ hath given the ministry, oracles, and ordinances of God, for the gathering and perfecting of the saints, in this life, to the end of the world: and doth, by his own presence and Spirit, according to his promise, make them effectual thereunto.[6]

Further, in chapter 26, On the Communion of Saints, Westminster states (emphasis mine in italics):

Saints by profession are bound to maintain an holy fellowship and communion in the worship of God, and in performing such other spiritual services as tend to their mutual edification; as also in relieving each other in outward things, according to their several abilities and necessities. Which communion, as God offereth opportunity, is to be extended unto all those who, in every place, call upon the name of the Lord Jesus.[7]

Yet again, the Westminster Confession (the fountainhead from which churches of the Scottish Presbyterian tradition trace their theological lineage) affirms that dictum that the gathering of the saints is the ordinary means by which Christian believers are discipled and matured and that to separate or purposely and obstinately absent oneself from this fellowship is to do so at the peril of one’s eternal state.

As with the other historic Reformed Confessions examined above, Westminster places a priority on the corporate ordinances and practices of the church as necessary for Christian health and discipleship, but it does not do so to the exclusion of acts of private or family piety. In chapter 21 of the Confession, Westminster states, “God is to be worshiped everywhere, in spirit and truth; as, in private families daily, and in secret, each one by himself; so, more solemnly in the public assemblies, [emphasis mine] which are not carelessly or willfully to be neglected….”[8] In this sentence, perhaps most pointedly, we see the importance of both private and public acts of piety stressed, but with the greater weight of emphasis placed on the public. Relatedly in chapter 21, the Confession states, regarding the Sabbath day, that it is to be kept by observing a holy rest and that it is to be “taken up, the whole time, in the public and private exercises of his worship, and in the duties of necessity and mercy.”[9]

For the sake of brevity, we have overlooked Westminster’s extensive comments and teachings on the nature of the church and the sacraments. Suffice to say that, quite in alignment with the previously cited confessional and theological expressions, the great onus of Christian living finds its expression in the corporate life of Christian discipleship: the centrality of Christian discipleship is in the communal ministries of worship, sacraments, fellowship and the like. The historic, Reformed, confessional position seems to be that, while Christian discipleship is certainly more than those corporate aspects, in order for one’s practice to be distinctly and legitimately Christian, it cannot be less than those corporate aspects.

Continuity and Contemporary Application

As I hope these last two posts have shown, Christianity is fundamentally a corporate religion. Scripture teaches that Christians have an absolute duty to be part of a gathered assembly for corporate expressions of Christian piety, for mutual edification, for accountability, and for legitimate, observable spiritual growth. The central acts of Christian piety (preaching, congregational singing, fellowship, baptism, the Lord’s Supper, corporate prayer) are actions that demand a gathered participation and in some instances are acts that are either nonsensical to be practiced in private (e.g. preaching) or unlawful to be practiced outside the context of the gathered church (e.g. baptism and the Lord’s Supper).

In short: corporate Christianity is essential Christianity. Scripture knows nothing of a lone-ranger, isolationist expression of the faith. Scripture demands a corporate expression to the faith. This reality is further affirmed by the historical testimony of the church, particularly in the days of the Post-Reformation when the church put forth perhaps her most thorough and robust confessional articulations concerning the nature of the church, her practices, her people, their duties, and her ordinances. Venerable thinkers in the church’s storied past such as Calvin in the days of the Reformation and men such as David Clarkson[10] in the subsequent, theologically-developed Puritan era gave added articulation and further insistence on this conviction. Later respected theologians and ecclesiologists have likewise affirmed this priority as cited above (Bavinck, Clowney, etc.).

Though it is in vogue in the present day for individuals to insist that they “love Jesus but cannot stand the church” or that they are sufficient in their spiritual practices by reading their Bible and praying privately, Scripture would seem to have no category for such a “Christian” and the history of confessional Christianity would seem to have little tolerance for such willful absenting from the gathered church and her corporate ministries. To be blunt, modern day “Christians” who claim to have no obligation to a local congregation or the communion of saints are deceived and in genuine spiritual danger, having sundered their communion from that entity which has historically maintained the self-understanding that “out[side] of [her] there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.”[11]

Moreover, it bears addressing, albeit briefly, the impact of this doctrine on contemporary understandings of communion and mutual edification. In recent years, in light of the COVID pandemic in particular, the issue of “virtual communion” or “virtual Lord’s Supper” has arisen: that is, is it required or necessary that one be physically gathered in a shared space in an assembled company of fellow Christians in order for the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper to be observed legitimately? Put another way, is it biblically legitimate to celebrate the Lord’s Supper via a livestream service, with the minister presiding over the sacrament from the church building, standing in front of a camera, with the scattered “congregation” viewing from afar via livestream and partaking of the bread and wine from the convenience of their living rooms?

Given what we've seen in this and the previous post, the answer is a resounding “no.” The communion of the saints that is articulated by both the apostolic, Scriptural testimony as well as the historical, confessional expressions assumes—yea, necessitates—a physical gathering and an assembled company of worshippers inhabiting a physical space together. To suggest that the New Testament might have ever hypothetically envisioned a scattered, satellite observation of the Lord’s Supper (albeit simultaneously) among a congregation is to stretch both the limits of reason as well as the bounds of grammar, an anachronism and eisegetical error of the highest order.[12]

Indeed, in his instructions regarding the partaking of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11, the apostle Paul employs the phrase “when you come together” (emphasis mine) in verse 17, from the Greek συνέρχεσθε, which the major lexica define as “come together, assemble, meet.” Other usages of this word in ancient literature are employed in the context of meeting in combat or battle, the coupling of animals, and sometimes even with regard to sexual intercourse between humans.[13] Suffice to say, the use of this verb translated as “come together” absolutely demands a physical expression of this reality, and not a virtual or metaphorical approximation.

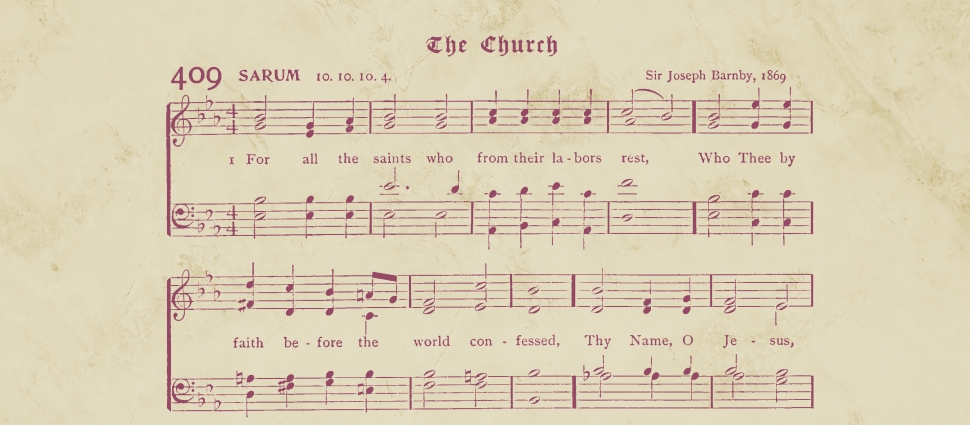

Along these same lines, the practice of mutual edification would also seem to demand a physical proximity of one believer to another. To cite but one example, we might look to the apostolic instruction in Ephesians 5 or Colossians 3 where Paul exhorts the believers to edify the body by singing to one another: “…but be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart,” (Ephesians 5:18b-19). Likewise, “…let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in one body. And be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God,” (Colossians 3:15-16). The question could arise as to whether the immediate context of these passages is that of Paul giving instructions regarding corporate worship per se, but that is a matter for another time.[14] The point remains that at this juncture in his epistles Paul is giving instructions for a shared life—corporate life and fellowship amongst Christians—and that this life entails mutual encouragement and edification.[15] According to Paul, part of that mutual encouragement and edification takes place in the form of Christians singing to one another so that the word of Christ would dwell in them richly.

Note also the deliberate imagery of body that the apostle employs in the Colossians 3: immediately preceding his instructions on singing psalms, hymns, and spirituals songs in order that Christians might teach and admonish one another in all wisdom (verse 16), Paul reminds them that they were called “in one body” (verse 15). Analogies, by their very nature, are meant to be illustrative of a more tangible reality. “Body” evokes an image of a bone-and-muscle, bonded physique. It is a metaphor, not meant to send the reader tunneling into infinite layers of figurative understanding, but an analogy meant to offer a better grasp of a true reality. The deliberate language there of inter-connectedness and mutuality is not to be ignored. The notion of Christians singing to one another and admonishing one another presupposes a physical proximity and a gathered situation. While modern audiences might like to conjecture that audio and visual technologies make possible the means whereby Christians could conceivably sing to one another while not being in the same physical space, certainly in the original first-century context of this admonition (absent any fanciful communicative technology) the notion of a non-gathered session of singing-edification would have struck the Colossians or Ephesians as nonsensical. For the apostle, singing, edification, and mutual encouragement among Christians requires a literal bodily proximity.

Thus, Christian fellowship and saintly communion demands a physical enactment. And if the administration of the sacraments are only rightly expressed within the context of a corporate assembly (as argued above), it follows that the administration of the sacraments is only properly observed within the physical, gathered company of believers. In short, so-called “virtual Lord’s Suppers” or “virtual baptisms” are wholly inappropriate and a conception entirely foreign to the Scripture. As well, the mutual edification of believers demands a fellowship of Christians that gathers “face-to-face.” Inasmuch as the incarnation was a true flesh-and-blood encounter of the God-Man with his people, so too is the faith founded by this God-Man a faith which demands flesh-and-blood-embodied fellowship among its adherents.

There is far more on this subject that can and should be addressed, particularly in applying this principle of Christianity's corporate nature to specific areas of Christian life (i.e. worship, discipleship, mission). But for now, I'm content to show that the corporate dimention of Christinity is both required by Scripture and congruent with historic Reformed thought.To live and to grow as a Christian is to live and grow as a member of the body. None of this is to deny the private dimensions of Christian spirituality. Yet there is a contemporary premium placed upon individual devotion and piety—a modern phenomenon which sometimes expresses itself deliberately apart from any tangible Christian community. This kind of “churchless Christianity” is entirely incompatible with the exegetical and historical testimony of Christianity.

Therefore, it is all the more incumbent upon Christian writers, pastors, preachers, theologians, and teachers to insist upon Christianity’s essentially corporate nature and to insist upon individual Christians’ adherence thereto. As much devotional literature has been published at the popular level which gives almost exclusive attention to one’s “personal walk with the Lord” (while important), just as much attention needs to be given to the churchly duties of one’s faith. Given the poor ecclesiology and biblical sensibilities of the present moment, it is incumbent upon church leadership to insist upon the duties and obligations consistent with church membership and to teach and instruct upon this greatly misunderstood subject in the midst of an ignorant generation. It is incumbent upon parachurch ministries and publishing houses to produce written devotional materials that complement (not necessarily counter) the outsized emphasis on individual piety so that Christians are better instructed both on their duties of individual and corporate piety. And it is incumbent upon ecclesiological theologians to be about the business of producing weighty consideration and treatment on this matter, to counter the great dearth that presently exists on ecclesiology within Christian scholarship, with particular attention given not merely to the doctrine of the church in the generic, but on the particular relevance of the Christian’s absolute requirement to be a part of the gathered communion of saints and the particular spiritual blessings that accompany that corporate piety. If the church begins to give adequate attention to these emphases of her ecclesiology, perhaps she can begin to counter the rabid and unhealthy individualism that has crept in amongst her members and begin to make advances for a more healthy Christian piety, individually and collectively, in the coming generation.

Sean Morris (@MrSeanGMorris) serves as a minister at Covenant Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and as the Academic Dean of the Blue Ridge Institute for Theological Education.

Related Links

Podcast: "The Metaverse Church"

"Satan’s Strategy #11: Stay in the Dark" by Robert Spinney

"The Forgotten Gift of Evening Worship" by Jim McCarthy

A Place to Belong: Learning to Love the Local Church by Megan Hill

What Happens When We Worship? by Jonathan Landry Cruse

Notes

[1] “The Second Helvetic Confession,” Christian Classics Ethereal Library, accessed November 9, 2021, https://ccel.org/creeds/helvetic.htm.

[2] “The Second Helvetic Confession,” https://ccel.org/creeds/helvetic.htm.

[3] “The Second Helvetic Confession,” https://ccel.org/creeds/helvetic.htm.

[4] “The Scottish Confession of Faith,” Presbyterian Heritage Publications, Still Waters Revival Books, accessed November 8, 2021, http://www.swrb.com/newslett/actualNLs/ScotConf.htm#CH16.

[5] While much space in each of the respective confessions is given to articulating the doctrines of Scripture, God, Christ the Mediator, and the order of salvation, so too much space is dedicated to articulating the essential and central role of the church and her ordinances (sacraments) in the life of Christian believers. The Scots Confession (1560) speaks of the Kirk (Church) in chapter 16 and proceeds to speak of the sacraments, their right administration and the rightful recipients in chapters 21-23. Likewise, the Belgic Confession (1561) speaks of the Church in Article 27, and proceeds to speak of Church Members’ obligations in Article 28, the Marks of the True Church in Article 29 and then the Sacraments, their right administration and the rightful recipients in Articles 33-35. So too, the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646) describes the Church in chapter 25, the Communion of Saints in chapter 26, and then offers teaching on the sacraments in general, and baptism and the Lord’s Supper specifically in chapters 27-29.

[6] “Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, accessed November 8, 2021, https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

[7] “Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, accessed November 8, 2021, https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

[8] “Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, accessed November 8, 2021, https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

[9] “Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, accessed November 8, 2021, https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

[10] David Clarkson’s “Public Worship to be Preferred over Private” in Works of David Clarkson (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1988) 3:187-209. This essay is a masterful, Puritan-era treatment of exactly the same topic being considered in this article, though it more narrowly applies to the subject of worship and it approaches the matter from a more exegetical-pastoral-theological approach rather than a systematic-theological approach as attempted here. Clarkson makes many bold and justified assertions such as, “Public ordinances are a better security against apostasy than private, and therefore to be preferred,” “[in public worship] are the clearest manifestations of God,” “There is more of the Lord’s presence in public worship than in private,” “Public worship is the nearest resemblance of heaven, therefore to be preferred,” and the like.

[11] Westminster Confession of Faith 25.2. “Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, accessed November 8, 2021, https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

[12] This line of reasoning likely bears on the legitimacy of so-called “simulcast preaching,” “multi-site worship,” or “satellite preaching,” but such a discussion warrants an entirely separate article.

[13] H. G. Liddell, R. Scott, H.S. Jones, & R. McKenzie, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 1712.

[14] Barry Clyde Joslin, “Raising The Worship Standard: The Translation And Meaning Of Colossians 3:16 And Implications For Our Corporate Worship,” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 17, no. 3 (2013): 50-58.

[15] FF. Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians (Grand Rapids:Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1984), 334.

For Further Reading

Allison, Gregg R., Graham A. Cole, and Oren R. Martin. The Church: An Introduction. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2021.

Allison, Gregg R., and John S. Feinberg. Sojourners and Strangers: The Doctrine of the Church. 1st edition. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2012.

Bannerman, James. The Church of Christ. Reprint. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2015.

Bavinck, Herman. Reformed Dogmatics: Holy Spirit, Church, and New Creation. Edited by John Bolt. Translated by John Vriend. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2008.

“Belgic Confession.” United Reformed Churches of North America. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://threeforms.org/belgic-confession-introduction/.

Benge, Dustin. The Loveliest Place: The Beauty and Glory of the Church. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2022.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together: The Classic Exploration of Christian in Community. 1st edition. San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009.

Bruce, F. F. The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians. Grand Rapids:

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1984.

Calvin, Jean. Calvin: Institutes of the Christian Religion. Edited by John T. McNeill. Translated by Ford Lewis Battles. Louisville, Ky. London: Westminster Press, 1960.

Clarkson, David. “Public Worship to Be Preferred Before Private.” Purely Presbyterian (blog), December 28, 2020. https://purelypresbyterian.com/2020/12/28/public-worship-to-be-preferred....

———. Works of David Clarkson. 3 vols. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1988.

Clowney, Edmund P. The Church. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1995.

Dever, Mark. Nine Marks of a Healthy Church. 4th edition. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2021.

“Heidelberg Catechism.” Accessed December 3, 2021. https://threeforms.org/heidelberg-catechism/.

Greggs, Tom. Dogmatic Ecclesiology: The Priestly Catholicity of the Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2019.

Helopoulos, Jason, and Foreword by Kevin DeYoung. Covenantal Baptism. Phillipsburg, New Jersey: P&R Publishing, 2021.

Hill, Wesley. “Why Personal Devotions Aren’t Enough.” ChristianityToday.com. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2014/december/why-personal-devotions-arent-enough.html.

Horton, Michael S. People and Place. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008.

Jamieson, Bobby. Built upon the Rock: The Church. 1st edition. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2012.

———. Committing to One Another: Church Membership. Study Guide edition. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2012.

Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti. An Introduction to Ecclesiology: Historical, Global, and Interreligious Perspectives. Revised and Expanded edition. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2021.

Leeman, Jonathan. Don’t Fire Your Church Members: The Case for Congregationalism. Nasville: B&H Academic, 2016.

———. One Assembly: Rethinking the Multisite and Multiservice Church Models. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2020.

Letham, Robert. Systematic Theology. Wheaton: Crossway, 2019.

Liddell, H. G., R. Scott, H.S. Jones, & R. McKenzie. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1996.

“Ligonier Ministries State of Theology 2020.” Ligonier Ministries. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://thestateoftheology.com/data-explorer/.

Lillback, Peter A. Saint Peter’s Principles: Leadership for Those Who Already Know Their Incompetence. Phillipsburg, New Jersey: P & R Publishing, 2019.

Nieuwhof, Carey. “Why Attending Church No Longer Makes Sense,” July 17, 2017. https://careynieuwhof.com/why-attending-church-no-longer-makes-sense/.

Pangritz, Andreas. Karl Barth in the Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Wipf and Stock, 2018.

Schaff, Philip. Fathers of the Third Century: Hippolytus, Cyprian, Caius, Novatian. Ante-Nicene Fathers: Volume 5.Edited by Arthur Cleveland Coxe. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017.

“Scottish Confession of Faith (1560).” Accessed December 3, 2021. http://www.swrb.com/newslett/actualNLs/ScotConf.htm#CH16.

“Second Helvetic Confession.” Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://ccel.org/creeds/helvetic.htm.

Tabb, Brian J. After Emmaus: How the Church Fulfills the Mission of Christ. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2021.

Waters, Guy P., Dane C. Ortlund, and Miles V. Van Pelt. The Lord’s Supper as the Sign and Meal of the New Covenant. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2019.

Waters, Guy Prentiss. How Jesus Runs the Church. Phillipsburg, N.J: P & R Publishing, 2011.

“Westminster Confession of Faith,” Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary. n.d. https://prts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Westminster_Confession.pdf.

Witmer, Timothy Z. The Shepherd Leader: Achieving Effective Shepherding in Your Church. First edition. Phillipsburg, N.J: P & R Publishing, 2010.