Erasmus & the Final Verses of Revelation

Let me begin by establishing the parameters of this little article. It is not an attack on the Textus Receptus or the Majority text from which the TR emerged. This article takes up a very specific historical issue, which can be summarized in a question. Did Erasmus back translate the last five verses of Revelation from Latin to Greek in his textual critical work or did he place the Latin in the Greek text as a placeholder until his publisher was able to find a Greek text containing those five verses. The former is what history has reported as truth and the latter is something I recently read which claimed that the historical account is false. This article seeks to decide between these two options.

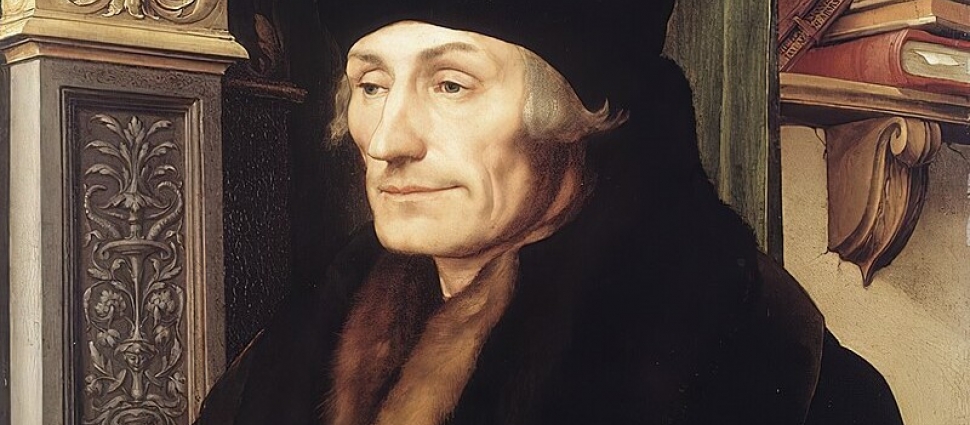

The Historical Account

In a 2016 internet article titled, “Erasmian Myths: Revelation Back-Translated from the Latin?,” Chris Thomas wrote the following, “There are many articles on the internet purporting to prove conclusively that Erasmus did in fact back translate from the Latin Vulgate the last few verses of Revelation.”[1] Thomas’s statement is misleading. It is not simply “articles on the internet” that make this claim but historians and scholars as well.

In Roland Bainton’s biography, Erasmus of Christendom, he writes of the Greek text(s) in Erasmus’s possession as the Dutch scholar completed the famous first edition of the Greek Bible, “The manuscript lacked the last five verses of Revelation which Erasmus himself translated from the Latin back into the Greek. He was promptly and properly criticized for this procedure.”[2] Bainton takes as his source an 1861 work of Franze Delitzsch titled Handschriftliche Funde.

Samuel Tregelles wrote in 1854 in his, An Account of the Printed Text of the Greek New Testament, when talking about Erasmus and those final verses of Revelation, “For the Apocalypse he had but one mutilated MS., borrowed from Reuchlin, in which the text and commentary were intermixed almost unintelligibly. And thus he used here and there the Latin Vulgate for his guide, retranslating into Greek as well as he could.”[3]

Frederick H. A. Scrivener wrote in, “A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament,” “As Apoc. 1 was mutilated in the last six verses, Erasmus turned these into Greek from the Latin; and some portions of his self-made version, which are found (however some editors may speak vaguely) in no one known Greek manuscript whatever, still cleave to our received text.”[4]

Even Edward F. Hills wrote in his, The King James Version Defended, “The last six verses of Codex 1r (Rev. 22:16-21) were lacking, and its text in other places was sometimes hard to distinguish from the commentary of Andreas of Caesarea in which it was embedded. According to almost all scholars, Erasmus endeavored to supply these deficiencies in his manuscript by retranslating the Latin Vulgate into Greek.”[5]

It should not be overlooked that even the website of the Trinitarian Bible Society, the publisher of the Textus Receptus shares this historical view. The website reads, “Erasmus has sometimes been criticised for his treatment of the last six verses of Revelation. The state of the copies in his hands made it impossible for him to edit this part of the text directly from the Greek, and he completed this portion by translating the Latin Vulgate back into Greek.”[6]

According to Thomas, the internet articles are misleading which purport that Erasmus back translated the final verses of Revelation from Latin to Greek. However, scholars from various periods demonstrate that both friend and foe of Erasmus shared the same view regarding his back translation. Erasmus clearly back translated from the Latin to the Greek and according to KJV defender, Edward F. Hills, some of that translation “still remains in the Textus Receptus.”

Thomas’s Case

Erasmus and Edward Lee were not friends and that is an understatement. The controversy between the two men was brewing for a couple of years before it went public in 1520. It is from this series of public invectives that Chris Thomas sites a work published by Erasmus against Lee. Here is the quote,

At the end of the Apocalypse, the manuscript I used (I had only one, for the book is rarely found in Greek) was lacking one or two lines. I added them, following the Latin codices. They were of the kind that could be restored out of the preceding text. Thus, when I sent the revised copy to Basel, I wrote to my friends to restore the place out of the Aldine edition; for I had not yet bought that work. They did as I instructed them. What, I ask you, do I owe to Lee in this case? Did he himself restore what was missing? But he had no text except mine. Ah, but he warned me! As if I had not stated in the annotations of the first edition what I had done and what was missing.[7]

At this point, Thomas writes, “So much for the supposed admission of back translation in his Annotations. The Greek for the last few verses (or just v 19 depending upon whom you read) was provided from the Greek manuscripts of the Aldine printers.”[8] In other words, Thomas argues that Erasmus inserted the Latin text and not a Greek translation of the Latin into his Greek pre-published text. Erasmus then sent his text off to the printer with instructions to replace the Latin in the final verses of Revelation with the Greek text from the Aldine edition. Presumably, this tactic of inserting the Latin was to give the printer a good guess as to how much room he would need for the Greek.

For Thomas the case is clear, but is it? A little examination will demonstrate that Thomas is confused about this Erasmian quote. First, Thomas is very confused about dates as we will see. For now, how could Erasmus have published the first Greek New Testament if there was an Aldine Edition of the Greek New Testament already published? Thomas is simply wrong here. Yet, Thomas seems to believe this because he mentions Erasmus’s Annotations, which were published with Erasmus’s Greek New Testament in 1516!

We should notice that the quote above has two different documents in mind. The first part of the quote deals with what Erasmus did originally with his pre-published Greek text, that is, he back translated from the Latin into Greek. Again, Erasmus wrote,

At the end of the Apocalypse, the manuscript I used (I had only one, for the book is rarely found in Greek) was lacking one or two lines. I added them, following the Latin codices. They were of the kind that could be restored out of the preceding text.

However, sometime later he sent a revised copy to Basel with instructions to use the Aldine edition for corrections to those final verses from the book of Revelation. According to Erasmus, he had not yet purchased the Aldine edition. Here again is the latter part of the quote.

Thus, when I sent the revised copy to Basel, I wrote to my friends to restore the place out of the Aldine edition; for I had not yet bought that work. They did as I instructed them.

Now, how might I prove that these two sections from the same quote refer to two different texts? Well, if Thomas is correct and the whole paragraph is talking about Erasmus’s pre-published Greek Testament then this passage makes no sense. Why? Because, as I’ve already said, Erasmus’s first edition was published in 1516 and the Aldine edition of the Greek testament was not published until 1518. Consequently, the first part of this paragraph must be talking about his pre-published text while the latter is talking about a revision sent to his publisher after 1518 when the Aldine edition was in print. It could be that the revision Erasmus mentions is his second edition which was published in 1519. However, Edward F. Hills says that Erasmus didn’t correct his back translation until the fourth edition, which would have put the date sometime before 1527. Nevertheless, this paragraph must have in mind a pre-published text and a later revision. To be clear, Thomas is wrong to think that this paragraph has in mind Erasmus’s pre-published Greek text.

Further proof for this view is a quote that appeared after the citation above in the debate between Erasmus and Lee. Here Erasmus speaks of his pre-published Greek Testament,

There was no doubt that the words had been omitted, and they were only a few. To avoid leaving a lacuna in my text, I supplied the Greek out of our Latin version. I did not want to conceal this from the reader, however, and admitted in the annotations what I had done. My thought was that the reader, if he had access to a manuscript, could correct anything in our words that differed from those put by the author of this work. ... And yet I would not have dared to do in the Gospels or even in the apostolic Epistles what I have done here. The language of this book is very simple, and the content has mostly a historical sense, not to mention that the authorship was once uncertain. Finally, this passage is merely the conclusion of the work.[9]

Here Erasmus, in a quote that appeared later in the debate between Erasmus and Lee, admits that he back translated from the Latin to the Greek in the Annotations of his pre-published Greek Testament.

Erasmus also mentions that he did not want to conceal the matter of back translating from the public, so he mentioned it in his Annotations, which accompanied the Greek Testament in 1516. What is more, Erasmus thought that the reader could make any necessary corrections if had access to a Greek manuscript. It is clear from this later quote that Erasmus back translated from the Latin into the Greek and to deny this evidence simply reduces the historical sequence to absurdity.

Some Final Thoughts

We should defend the Word of God. The Bible is God’s infallible and inerrant Word, and it is authoritative for our lives. However, the defense of the Biblical text cannot be reduced to the defense of a handful of manuscripts when God mediately preserved over five thousand manuscripts. What is more, when we defend a position, like the one Thomas is trying to defend, which is indefensible, we then cast doubt on our defense of the Bible. We unnecessarily jeopardize our witness rather than admit we are in error regarding a historical position.

I want to reiterate. This article is not in opposition to the Textus Receptus and it is certainly not in opposition to the Majority text, but it does take issue with a wrong interpretation of the facts of history that are demonstrably wrong. The fact is that Erasmus back translated from the Latin into Greek and some of that translation remains in the Textus Receptus to this very day.

Jeffrey A Stivason (Ph.D. Westminster Theological Seminary) is pastor of Grace Reformed Presbyterian Church in Gibsonia, PA. He is also Professor of New Testament Studies at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh, PA. Jeff is the Editorial Director of Ref21 and Place for Truth both online magazines of the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals.

[2] Roland Bainton, Erasmus of Christendom, (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2016), 140.

[3] Samuel Tregelles, An Account of the Printed Text of the Greek New Testament, (London, 1854), 21

[4] Frederick H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, ed. Edward Miller (George Bell & Sons, London, 1894), 296.

[5] Edward F. Hills, The King James Version Defended, (Des Moines, Iowa: The Christian Research Press, 1984), 202. Hills adds that Erasmus corrected his translation of the Greek in his 4th edition. However, writes Hills, “[but] he overlooked some of it, and this still remains in the Textus Receptus.” Cf. https://gentlereformation.com/2022/09/08/edward-hills-a-strange-providence/

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Collected Work of Erasmus 72, Translated by Erika Rummel, (University of Toronto Press, 2005), 344.