Chapter 21.7

June 6, 2013

vii. As it is the law of nature, that, in general, a due proportion of time be set apart for the worship of God; so, in His Word, by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment binding all men in all ages, He has particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto him: which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week: and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week, which, in Scripture, is called the Lord's Day, and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath.

The final two sections of chapter twenty-one refer to the principle of the Sabbath. Although no significance is now afforded to place, a significance still attaches itself to time. 21:7 assert explicitly a principle of Sabbath continuity from Old Covenant into New Covenant. The Sabbath principle is a moral and perpetual commandment of God, written into the fabric of creation itself and therefore binding upon society as a whole. Before it adopted specific Mosaic (and therefore temporal considerations relating to that period of redemptive history when the people of God were "under age" and a theocracy), the Sabbath reflected God's rest from labor in creation itself. At the resurrection of Christ, the day was changed to the first day of the week. The Confession does not address the issue as to whether this change is merely "recorded" (description) or specifically "mandated" (prescription). Technically, under the New Covenant, there is an observance of the Lord's Day - the first day of the week rather than the last day of the week (reflecting a gospel logic: rest followed by work rather than work followed by rest). This is to be observed to the end of the world.

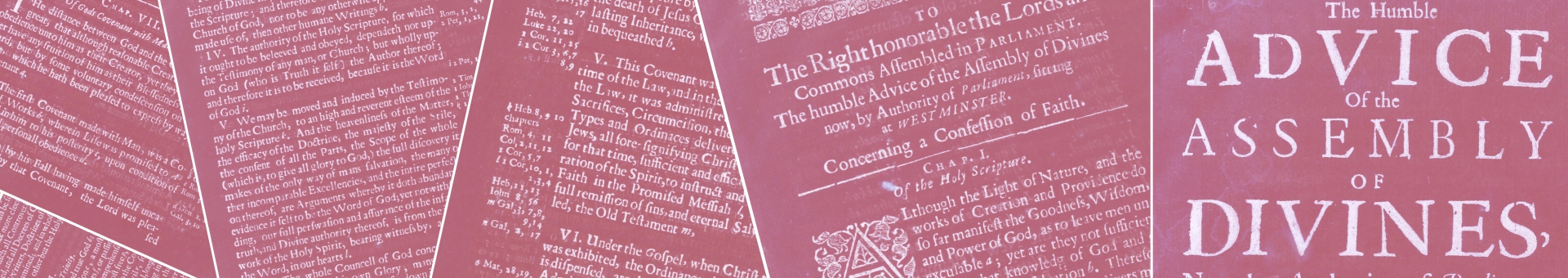

The Divines approbation of a "law of nature" might be viewed as a step beyond merely attributing the fact that the Sabbath was a law of creation - therefore observed in principle before the Mosaic Decalogue (note the word "remember" in Exodus 20:8 and the non-provision of manna on the seventh day because it was given as a Sabbath (Exod. 16:22-30)0. That the Westminster Divines (following in the wake of the Reformers and mainstream medieval thought in general) believed in the existence of natural law is beyond refute. There is insufficient evidence here to answer how natural law relates to Scripture (if at all).

What is clear is that the Sabbath is viewed as beneficial for man qua man - in what we might call "secular" society (and therefore civil enforcement) as well as the church. The Confession sees no change in principle as to applicability of the Sabbath principle in secular society (all men" and "all ages"). The change of day notwithstanding - with Aquinas, the Confession views it as merely a different way of counting six-and-one. There seems no room for Seventh Adventist views of the consecration of a Saturday Sabbath and even less for the "antinomian" (utilitarian) argument that "any" day (or part of a day) will do since we clearly have a need to gather together at some point on time. Mere tradition is inadequate. There exists a "positive, moral and perpetual commandment" for the continuation of the Sabbath principle in the New Covenant economy. Positive addresses the issue of the regulative principle - it is something for which a prescription exists. Moral suggests that sanctions apply. There is an "oughtness" to the keeping of the Sabbath Day. And perpetual suggests that any dispensational argument confining the Sabbath to the Mosaic economy is ruled incorrect.

Dr. Derek W.H. Thomas is minister of preaching and teaching at First Presbyterian Church, Columbia, South Carolina and Distinguished Visiting Professor of Systematic and Historical Theology at Reformed Theological Seminary.