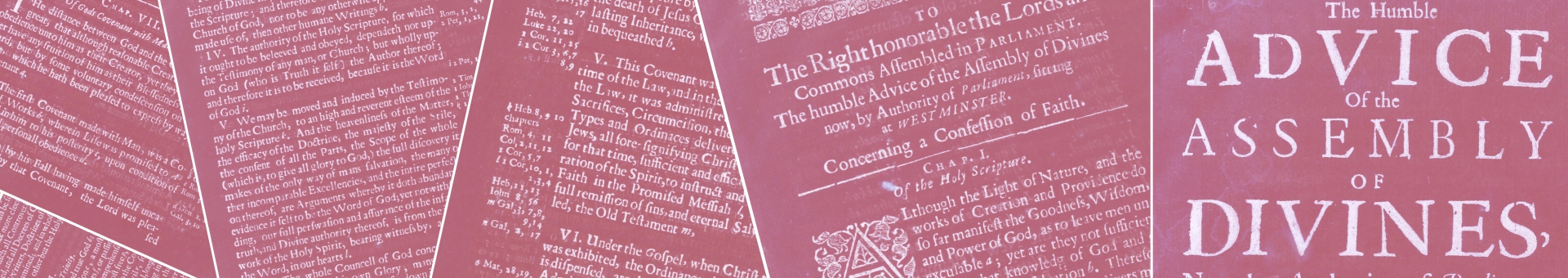

Chapter 2.1, Part One

January 21, 2013

i. There is but one only living and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions; immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, almighty, most wise, most holy, most free, most absolute, working all things according to the counsel of His own immutable and most righteous will, for His own glory; most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin, the rewarder of them that diligently seek Him; and withal, most just, and terrible in His judgments; hating all sin, and who will by no means clear the guilty.

Without parts... Really? Yes, for in this expression, the Westminster Divines affirmed the classical doctrine of divine simplicity. Subscribers to divine simplicity argue that if God were composed of parts, he would be dependent upon those parts for his being, thus making the parts ontologically prior and the affirmation that he "most absolute" (the main point of 2:1) impossible. Divine simplicity insists that God is identical with his existence and that every attribute is ontologically identical. Put another way, there is nothing in God that is not God. God is wholly and totally involved in everything that he is and does.

There is nothing particularly Reformed or Calvinistic about this affirmation. Thus Aquinas asserts "every composite is posterior to its components: since the simpler exists in itself before anything is added to it for the composition of a third." (Scriptum super libros Sententiarum, I.8.4.1). As with the chapter on Christology, for example, the Confession is affirming traditional theism. To err here means to deviate from Christianity itself. Richard Muller confirms this: "The doctrine of divine simplicity is among the normative assumptions of theology from the time of the church fathers, to the age of the great medieval scholastic systems, to the era of Reformation and post-Reformation theology, and indeed, on into the succeeding era of late orthodoxy and rationalism." (Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, III: 39).

Detractors (Alvin Plantinga and Ronald Nash come to mind) notwithstanding, the Divines maintained divine simplicity as essential doctrine. For a first-rate analysis, see James E. Dolezal, God Without Parts: Divine Simplicity and the Metaphysics of God's Absoluteness (Pickwick, 2011).