Two Sisters, a Desert Monastery, and a Palimpsest

Tourists travel from all over the world to experience the expansive deserts, remote wildernesses, peoples, foods, and sites of north Africa and the Middle East. Many of these (occasionally naïve) travelers have been drawn to the region by the adventures of Lawrence of Arabia or Indiana Jones, only to find the climate inhospitable and travel treacherous.

But before the days of Hollywood, two sisters made their way across daunting, arid terrain to a remote monastery at Mt. Sinai—and there they discovered a treasure that would make even the most daring archeologist marvel. The sisters expressed the purpose of their expedition in the published account of their trip, How the Codex was Found:

“[We] resolved to carry out our long-cherished plan of visiting the scene of one of the most astonishing miracles recorded in Bible history— a miracle which has hitherto baffled the most determined opponents of the supernatural in history to explain away; the passage of the Israelites through the desert of Arabia, and the spot where a still more impressive event occurred, the secluded mountain-top where the Deity first revealed Himself to mankind as a whole, not simply to the few chosen ones whom He had, from time to time, consecrated to be the exponents of His will to their fellowmen” (pp. 6-7).

Who were these women that embraced such an excursion because of supernatural interests in an era of higher criticism that disparaged the inspiration and infallibility of Scripture by challenging the reliability of its textual sources? Their home was the coastal village of Irvine, Scotland, just a jaunt south of Glasgow. They were born April 16, 1843 to John and Margaret (Dunlop) Smith. Agnes entered the world before her identical twin sister Margaret Dunlop, but the joy brought by the two babies was soon turned to mourning by the mother’s death a few weeks later. It was a difficult situation for John, but fortunately he was of sufficient means to hire help to care for the twins.

As Janet Soskice notes, the girls were brought up “intensely Presbyterian” with Sabbath observance and worship, while their education at Irvine Royal Academy was augmented by their father (Soskice, 10). John, clever tutor that he was, struck a deal with his daughters: For each foreign language they learned, he would take them to the corresponding country. The girls acquired French, German, Spanish, and Italian at an early age then visited the respective nations (Soskice, 9). Learning languages would be a life-long endeavor for Agnes and Margaret, and it would prove important for their trip to Mt. Sinai.

It was in the closing months of 1891 when Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson prepared for their journey. Both their husbands had passed away, so they traveled and studied for the remaining years of their lives. The inheritance left by their father gave them freedom to follow their interests. They had traveled to the eastern Mediterranean previously, including several trips to Egypt, with one that extended to a year. Friends encouraged the two to pursue the trip.

One person in particular was quite helpful, J. Rendel Harris, who was enthusiastic about their textual interest and trip, though likely not so sympathetic to their supernatural motivation. Harris had recently discovered in the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai written in the Syriac language within a codex a copy of Apology for the Christian Faith by Aristides. Note that a codex is made of several sheets of parchment stitched together at one edge; it is the transitional textual form from scrolls to bound books. He told the sisters that other Syriac texts were held there, but he did not have time to look at them. He was especially helpful to the sisters because he taught them how to use a camera and built a stand for them to hold a codex open for photographing.

The two arrived in Cairo, Egypt where they sought permission from the Greek Orthodox Church to access the manuscripts in St. Catherine’s. They had a referral from Cambridge University and letters of introduction to help them along the way (Soskice, 114). While getting things in order, they took the opportunity to visit an exhibition of artifacts from Rameses II which had been discovered in 1881.

Whatever may be said in the way of discrediting the histories narrated in the Old Testament, it must henceforth be impossible for the most hardened sceptic to deny that the Pharaohs, at least, have existed. (9)

Meanwhile, their petition to the church authorities was successful, with the Archbishop of Mt. Sinai granting permission to access the monastery. He gave the women a letter of reference, advising the monks to provide every courtesy to the ladies. With paperwork in hand, Margaret and Agnes crossed the Gulf of Suez in a sailboat in January 1892.

The trek to Mt. Sinai required a guide (called a dragoman) named Hanna. There were also helpers who were Bedouin (nomadic people), and another man they called sheikh. The sisters in a caravan of camels burdened with baggage, tents, food, and photographic equipment set off on their journey. Even though Agnes and Margaret had previous experience with camels, they found it difficult to read the Psalms in Hebrew as they bounced along. By the time they reached an area of palms that was said to be the place where Miriam sang her song (Ex 15:20-21), it was four o’clock. They went on a bit further and camped that evening. The next day the journey continued.

"[O]ver very stony ground, where a few tufts of sapless heath or of spiky thorns enticed our camels to stop and nibble. Sometimes the ground was sprinkled with flakes of shining white quartz, suggesting manna" (17-18).

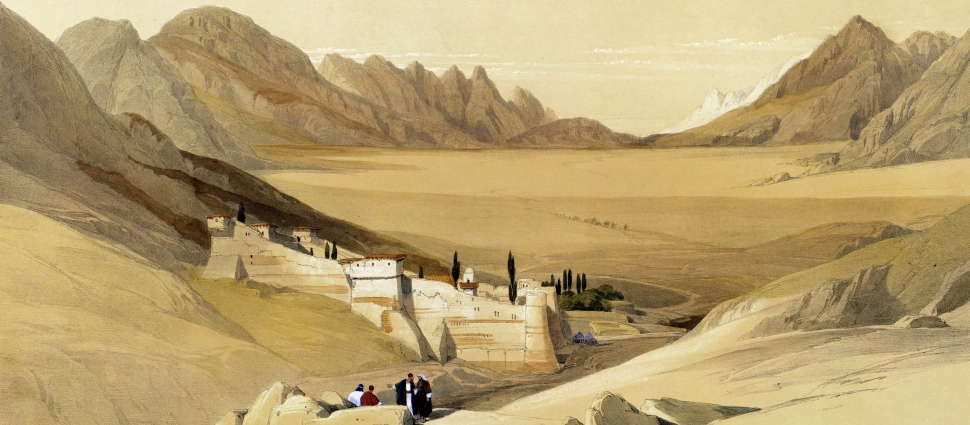

Camping once again for the night, they continued the next day and at one point crossed a rocky ridge where the camels had difficulty with their footing, but they struggled along while the sisters enjoyed the scenery. Further on, the sand color became pink with cliffs made of black rock and red sandstone topped by peaks of pink granite. Several times sites passed by were said to be locations of events from Scripture, such as the place where Moses struck the rock (Numbers 20:11) and the position where he viewed the battle with the Amalekites while Aaron and Hur held his hands up to obtain victory (Exodus 17:12). They passed through an oasis and continued until they saw the monastery in the distance.

The monastery stands clinging to granite some 2800 feet below the summit of Mt. Sinai. It is a mixture of buildings from different eras with the great wall that surrounds it having been built for a fort by Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the fifth century. Once they arrived at the monastery, they made camp among trees on the property outside of the walls. They were courteously welcomed by the prior and an important resident for their work, the librarian Galaktéon, was particularly congenial when he found out they were friends of J. Rendel Harris.

Margaret and Agnes began work with the manuscripts Monday, February 8, spending the entire day looking over Greek, Arabic, and Syriac texts within the library along with others scattered in various rooms of the complex. Unfortunately, the parchment documents had suffered from storage in a damp pit during some eras of their history, but they were still legible. Galaktéon was immensely helpful sometimes holding the pages open for photographing. The monastery was not an easy place to work in during February. The days could be temperate and comfortable but at night the temperature could plunge below freezing with high winds creating an icy chill in their tents. However, the challenging climate was balanced by the stunning sunsets when the cypresses towering above the masses of white almond and olive trees were aglow.

In the midst of their work among the manuscripts, they took a day to climb with the help of a guide to the site where God met Moses on Mt. Sinai. They could not access the rock where God spoke, but they could view it from their position and see across the extensive and beautiful plain spread before them. When they made it back to the monastery, the trip had taken eleven hours of walking over rocky and rugged terrain. They were tired and sore from the climb, but felt their effort was rewarded. They had seen the site where God and the prophet Moses met.

They examined several Arabic and Greek documents, but it was a Syriac one that proved most important. They photographed the remaining pages of the Syriac Codex where Harris found the Apology of Aristides, but then there was another codex that garnered their attention—a palimpsest.

A palimpsest might be considered recycling today. It is a parchment scraped of its original text and then used for a new manuscript. Writing media was expensive and at times scarce, so if a new document was to be made a scribe would locate a text no longer needed and repurpose it. The original text of a palimpsest that is scraped away is called underwriting, and the newer text is overwriting.

But this raises a question: If the original text was scraped off, how did the sisters perceive the presence of underwritten text?

As the centuries pass, environment and age cause the remnants of original ink to appear with varying degrees of clarity within the new text. In some cases the underwriting can be seen between the lines of overwriting, while in others the under- and overwriting are at right angles, or even on top of each other. In the case of the codex they discovered, the undertext was red ink that contrasted with the ink overwritten. As the Scottish sisters worked their way through the palimpsest, they found a new use for their tea kettle.

"Its leaves were mostly all glued together, and the least force used to separate them made them crumble. Some half-dozen of them we held over the steam of the kettle. The writing beneath is red, partly Syriac and partly Greek. The upper writing of this palimpsest bears its own date, A.D. 698 [778, more probably] it is all the lives of women saints. The under writing must be some centuries earlier; it is Syriac Gospels, and something in Greek, not yet deciphered" (52-53).

Agnes was the only one of the three who could read Syriac, so she discerned the underwriting was in fact the four Gospels. It was quite a find, especially since two non-professionals made the discovery. All the pages of the Gospels were photographed and packed with the other rolls of film for the trip home.

They left the Monastery of St. Catherine March 8, following a different route than the one by which they arrived. Dragoman Hanna was in a rush and hurried the caravan along. The sisters wanted to stop for the night in the afternoon, but Hanna pressed them on until by moonlight camp was made on rocky ground that was too hard for driving stakes. Rocks were piled on the rope tent stays to keep them secure. They continued on through the stony ground the next morning with both sisters dismounting to walk because of the irregular gait of the camels caused by walking on stones. Then they traveled five hours across the deep white sand. On Saturday night, they made camp at Wadi Ghurundel, and despite an incident where the wind carried the tent up from the ground, the two sisters were able to catch some sleep.

The next day they started a two-day stretch, walking over “sandy plains, where we suffered greatly both from heat and thirst” (65). The sisters insisted that Hanna pitch the tent for lunch to provide shade, but the tent did not keep the wind from blowing sand all over them and their food. Water was hard to come by, and when found it needed to be purified with a filtering device. One Bedouin was so parched he quickly drank unfiltered water he found trickling from limestone that made him quite ill later (magnesium sulphate in the water). They made it to their last encampment that night and once again the wind blew, shaking their tent and beds throughout the night. Margaret’s foot was injured during the journey and it troubled her considerably. Late in the morning, the Gulf of Suez was sighted on the horizon resulting in a shout of joy from all.

"We learned to appreciate the full meaning of one of the blessings which God bestowed upon the Israelites during their forty years' wanderings in a region where the strongest English made boots soon give way on the rough granite stones: 'Thy raiment waxed not old upon thee, neither did thy foot swell these forty years.' 'I have led you forty years in the wilderness,' said Moses. 'Your clothes are not waxen old upon you, and thy shoe is not waxen old upon thy foot'" (pp. 68-69).

Once they crossed Suez, Agnes and Margaret boarded the steamer Saghalien that would take them to Marseilles where they could cross France and head home. Settled on deck as they departed, they could remember the arduous trip and contemplate the fruit of their labors and the importance of what would be called the Sinaitic Palimpsest. They made it back to their home in Cambridge safely with all the film undamaged. At the suggestion of a friend, they took a roll of film to a professional for developing, but the twenty-four images of pages were disappointingly faint and illegible. The sisters set up their own darkroom, developed the rest of the film themselves, then realized a curious thing had happened.

One day while photographing the palimpsest at St. Catherine’s they lost their place in the page sequence and had to figure out where the photographing should continue. They located what they thought was the next page in the sequence, began shooting again, and once the pictures were developed in Cambridge they realized they had duplicate photographs of some of the pages. The duplicates included the twenty-four faint images processed by the photo shop which meant their confusion at the monastery led to a back-up set to replace the images misprocessed. Could this accidental duplication in fact be what the Westminster Standards describes as “a special providence?” Their photographs proved beneficial, but it was clear from the opinions of scholars that a return to the Monastery of St. Catherine was necessary. A return trip was planned almost immediately, and the second half of How the Codex was Found provides an account of that trip.

It is a remarkable story. Sisters without doctorates in philology or ancient languages and apparently no financial backing other than their own wealth, took off on a challenging trip. Their interest in visiting Sinai was supernatural, driven by the desire to see where the Exodus took place and where God spoke to Moses on the mount, but with Harris’s discovery of Aristides’s Apology and his encouragement to visit the trove of manuscripts at St. Catherine’s, they were inspired into action. As for the importance of the Sinaitic Palimpsest, at the time it was the oldest known Syriac text. Another important aspect is the Sinaitic Palimpsest shows the relationship of the Syriac text to the oldest Greek and Latin ones. Ancient Biblical manuscripts are important because they show the spread of Scripture throughout the ancient region. In the case of the palimpsest, the text of the Syriac Gospels has been interpreted by some as corrupted to deny the full divinity of Christ in some passages. It may be shocking to think that an insensitive scribe would have overwritten the Gospels with non-inspired material, but could there have been a good reason for the action? Did a scribe scrape away the set of Syriac Gospels to use the parchment for biographies of women saints because he knew the evangelists’ text was corrupted? Was he ending transcription of the text into successive corrupt copies?

The Westminster Confession affirms that all books of the Bible were “immediately inspired by God, and by his singular care and providence kept pure in all ages, and are therefore authentical” (1:8). So, what appears to have been vandalism of the Word of God could have been a providential work of piety by nameless but dedicated scribes. The remarkable story of the sisters Smith, their manuscript discovery, and their continued concern as Presbyterians holding to the supernatural Scripture should not be forgotten.

Barry Waugh (PhD, WTS) is the editor of Presbyterians of the Past. He has written for various periodicals, such as the Westminster Theological Journal and The Confessional Presbyterian. He has also contributed to Gary L. W. Johnson’s, B. B. Warfield: Essays on His Life and Thought (2007) and edited Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I (2012).

Related Links

"The Digitization of Sinaiticus and its Media Beepbop" by Nicholas Perrin

"Church History's Greatest Myths" by Ryan M. Reeves

"How Jesus Became God," reviewed by Michael Kruger

The Case for Biblical Archaeology by John Currid

Why These Books and No Others?, with Michael Kruger and Richard Phillips

B. B. Warfield Memorial Lecture Series Anthology, with Iain Murray, Gregory Beale, and John Currid

Notes

The full information for the sisters’ book is, How the Codex was Found: A Narrative of Two Visits to Sinai from Mrs. Lewis’s Journals, 1892-1893, Cambridge: Macmillan and Bowes, 1893, the content of the book was first published in “the columns of the Presbyterian Churchman.” “Soskice” refers to The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels, New York: Vintage Books, 2009, by Janet Soskice, which provides biographical information and tells the story of the Syriac Gospels and the remainder of the sisters’ lives. Agnes Smith Lewis published an English translation of the palimpsest, and her introduction provides information about its discovery, see A Translation of the Four Gospels, from the Syriac of the Sinaitic Palimpsest, London: Macmillan, 1894; the sisters went on to publish other titles related to the palimpsest as well as translations of other manuscripts including Arabic. Portraits of the identical twins are available at the Cambridge University site, Cambridge Past, Present & Future. Camel and dromedary are used as synonyms; single hump camels are domesticated in the region of Sinai. There is a collection of lantern slides of the sisters’ journey available at “Sisters of Sinai Travel Lantern Slides” in the University of Cambridge Digital Library; just click through the 288 photographs. The precise dating of the Sinaitic Palimpsest has proven elusive with the limited sources available to this author. Much of the manuscript cataloging and analysis material is within copyright and unavailable to me. It appears the most popular date is the fifth century, but it certainly can be no later than the date of the overwriting of Aristides’s work. The mid-second century date is from W. F. Farrar’s article “The Sinaitic Palimpsest of the Syriac Gospels,” in The Expositor 1:1 (Jan. 1895), 1-19; but I am not sure what he means by “form of” as he refers to the date.