The Trial of Patrick Zaki

When I told a friend in Italy that I was not familiar with the name Patrick Zaki, he was surprised. Zaki’s name has appeared frequently in the Italian news ever since his arrest in Cairo, Egypt, about nineteen months ago. And the news media continue to follow as his trial is repeatedly postponed.

Zaki has particularly caught the attention of Italians because he has studied there, at the University of Bologna, the oldest university in the western world. And his name has filled the news because his arrest appears to be as unjust as the discrimination he denounced.

Zaki’s Imprisonment

Zaki was born on June 19, 1991 in Mansura, Egypt, to a family of Coptic Christians. After completing his studies in Egypt, he went on to study for a Master degree in Bologna. He was arrested at the Cairo airport on February 7, 2020, as he traveled home for a visit.

The next day, a local court condemned him to a temporary imprisonment on five charges: threat to national safety, incitement to illegal demonstration, subversion, spreading fake news, and promoting terrorism. The reason? An article Zaki wrote in 2019, published under a pen-name on the Egyptian website Darraj.

“Not a month goes by without painful incidents against Egyptian Copts, from attempts at to displace them to Upper Egypt, to kidnappings, to a church closure or a bombing attack,” he wrote. “This article is a simple attempt to follow the events of a week in the daily life of Egyptian Christians, as reported in their diaries.”

The article goes on describing some of these events, specifically the infringement of constitutional rights in matters of inheritance, the refusal to give Christians due public recognition, and the dismissal of their testimonies in a court of law, simply because they are Christians.

According to Amnesty International (quoting one of Zaki’s lawyers), the young man was kept blindfolded and handcuffed for 17 hours during his interrogation, when he was also threatened, beaten and tortured with electric shocks. He was later detained, with the date of his trial postponed twice. At a recent hearing on September 28 in Mansura, a new date was set for December 7.

The prosecution has initially asked for a sentence of five years in prison, which is what has been previously decreed for other men in similar situations. But the insistence on charges of subversive and terrorist propaganda could extend the sentence to 25 years or a lifetime.

Zaki’s lawyer, Hoda Nasrallah, sees a positive turn in the fact that her legal team is finally able to see an official copy of the proceedings, which had until now been kept secret.

Meanwhile, representatives from several European nations and various organizations have asked the Egyptian authorities for an immediate release of Zaki, stating that his imprisonment is without legal justification. In an official statement, a group of organizations called this attack on Zaki “an infringement on the rights of all Egyptians to freedom of expression, and the rights of Christian Egyptians in particular to demand their right to equality both socially and in front of the law.”[1]

Diplomats from Italy, Spain, and Canada were allowed at Zaki’s latest trial, while Germany and the US have indicated in writing that they are monitoring his case. In the meantime, the Italian government is deliberating the possibility of granting him citizenship.

The Egyptian Copts

Copts represent the largest religious minority in Egypt. Estimates of their numbers range from 5 to 11 million. Historically, they are one of the oldest ethnic groups to adopt Christianity. They have been kept distinct from other Christians by their language and their refusal to adopt the decisions of the 451 Council of Chalcedon regarding the two natures of Christ.

The word Copt comes from the Arabic Qiht, a shortening of the Greek Aigyptos, an indication that Coptic was the original Egyptian language, written first in hieroglyphics and later in Greek letters. With the exception of Alexandria, where people spoke Greek, Coptic was the language of Egyptian Christianity. The Bible was translated into Coptic at an early stage, together with other Christian writings. Famous monastic leaders of the fourth and fifth centuries, such as Antony, Pachomius, and Shenoute, spoke Coptic.

Today, most Copts belong to the Coptic Orthodox Church. Few adhere to the Coptic Catholic Church or to Evangelical churches.

Persecution or Discrimination?

During a TV interview in January 2021, Patriarch Tawadros II, the spiritual head of the Coptic Orthodox Church, denied that Copts are persecuted, a word that is best matched to situations of systematic violence and restrictions as we find in countries such as Afghanistan or North Korea, or as were frequent in Egypt at the time of Perpetua and Felicita.

This denial was confirmed by the 2019 Country Policy and Information Note on Egyptian Christians, published by the UK government. The report recognizes that the Egyptian government has made some improvement in their anti-discrimination policies. “However,” it continues, “despite positives trends, Christians continue to face societal discrimination and, occasionally, violence, including by armed groups, although this is largely confined to rural areas. There is limited information about those Christians who proselytize or the treatment of Christian men involved with Muslim women, but Christian converts face high levels of societal discrimination.”[2]

This discrimination manifests itself in various ways. For example, Egyptian Christians have historically been denied promotions to certain jobs, have been underrepresented in government media and job positions, and are required to work on Sundays. Although a 2016 law has lessened its restrictions on the building and remodeling of churches, these restrictions can still be applied at will by local governors. In fact, at least 25 churches have been closed since 2016.

But the distinction between discrimination and persecution has often been flimsy. Was the 2011 Maspero Massacre an act of persecution, when a peaceful protest for the destruction of a church in Upper Egypt was crushed by the army and security forces, resulting in 24 deaths and 212 injuries? Was it persecution when Islamic extremists attacked St. Mark’s Cathedral, the most sacred building for millions of Coptic Christians, in 2013? Was it persecution when the agents who came to keep the peace in that instance killed two Christians and wounded dozens of others?

Whether we call them persecution or discrimination, attacks by Islamic extremists have continued. In 2015, the terrorist group Daesh kidnapped and killed 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians who were in Lybia as migrant workers. Two years later, 45 Christians were killed during two Islamic suicide bombings in churches in Alexandria and Tanta, Egypt. The largest attack was in 2013, when crowds of Islamic extremists attacked at least 42 churches, burning or damaging 37, and leaving four people dead. In most cases, human rights organizations have denounced the passive attitude of the Egyptian government.

Fear of Reporting

While many Egyptian Christians recognize that the present government has made more efforts to end discrimination than any of the previous ones, Egyptians who report on current episodes of religious discrimination and other human rights violations still face heavy penalties.

This is largely due to the vague wording of Article 80(d) of the Egyptian Penal Code, which states that any Egyptian who “deliberately discloses abroad false or tendentious news, information, or rumors about the country's internal situation” may face up to five years in prison.

Patrick Zaki is not the first one to be punished under this legislation. Saadeddin Ibrahim, a sociology professor at the American University in Cairo, and Ahmed Samir Santawy, a student at the University of Vienna, were detained under charges similar to Zaki’s. Ibrahim, arrested in 2001, was sentenced to seven years, and Santawy, arrested in 2019, to four. Coptic activist Ramy Kame, arrested in 2019, only a few days before he was scheduled to speak in the United Nations Forum on Minority Issues, is still detained and reportedly in poor mental health.

Given the ambiguity of this law and the fact that it can be interpreted at will, it’s no wonder that many Egyptian Christians are reticent to speak out.

“Please God, help everything to go well,” Marise Zaki, Patrick’s sister, wrote on social media before the September 28 trial. We can join her prayers for her brother, for all Christians in Egypt, and for a fairer legislation that can protect rather than punish the Egyptian church.

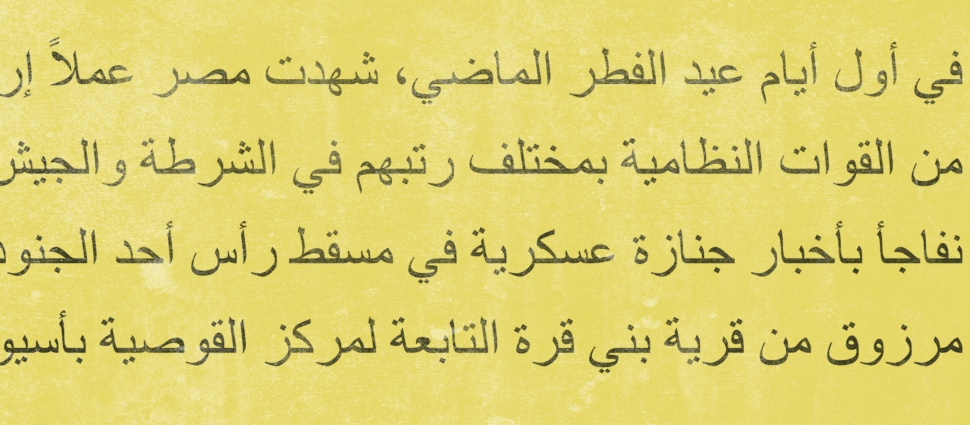

Editor's Note: The text in the header image comes from the first paragraph of Zaki's Daraj article, available here (in Arabic).

Simonetta Carr is a mother of eight and a homeschool educator for twenty years. She has also worked as a freelance journalist and a translator of Christian works into Italian. Simonetta is the author of numerous books, including Weight of a Flame and the Christian Biographies for Young Readers series.

Related Links

"A Prayer for Persecuted Brethren" by Chad Van Dixhoorn

"The Persecution Driven Life" by Dustin Benge

"Pablo Besson - For the Gospel and Religious Freedom" by Simonetta Carr

Hebrews by Eric Alexander

Notes

[1] https://eipr.org/en/press/2021/09/after-19-months-pre-trial-detention-pa...

[2] Home Office, UK, Country Policy and Information Note Egypt: Christians, 2.4.9.