Some Suggestions for Songs

In our last post, we saw why songs for congregational singing need to have biblical content, as well as music suitable for active participation. We have also seen how worship should be conducted for the glory of God and the building up the Christian community. With all of this in view, we can now consider some more detailed features in music which encourage active participation from the congregation. Once again, I am expressing my opinions, and others may certainly disagree. My purpose is to encourage us to think through the reasons for our decisions, and to make sure that we keep in mind the long-run goal of the glory of God and the building up of the church.

Qualities That Promote Singability

May I suggest that the need for singable music leads in some different directions from the concerns of performance? As always, we need flexibility. But we also need thoughtfulness. What helps a song to be singable?

First, with some possible exceptions, singable music has a regular time signature. 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, and 6/8 are standard in traditional Western music. When untrained people try to sing to these meters, they soon catch on. By contrast, irregular meters can be frustrating. Of course, people can eventually learn. But my perception is that it takes more time. And that kind of extra attention to an irregular meter may distract them from participating more fully in the content. In addition, many Christian songs in the West have a larger rhythmic pattern, such as "Common Meter" (8.6.8.6), or "Long Meter" (8.8.8.8), or 7.7.7.7, or 11.10.11.10 ("Finlandia"), or some other fairly simple pattern.

Syncopation (giving stress to a normally weak beat) seems to me to be popular in quite a few instances of Christian music. There are many people who like it. It may be engaging precisely because of breaks in the normal pattern, and some people may find it easier to connect emotionally to such music. But it may also be more difficult to sing. The untrained men and women in the congregation are not going to know when to begin the next word, and so they will be dependent on the leading musicians in a way that is far from ideal. This disadvantage must be considered.

A similar principle also gives us caution about musical interludes, either between stanzas or as a one-time transition leading to the final stanza of a song. This kind of interlude is perfectly fine in a performance. But a congregation does not always know when to come in. Even if it is the same interlude after each stanza, the congregation does not know when to begin again unless there is a clear musical signal that the interlude is coming to a definite, well-marked end.[1] And even if an interlude has a clear musical terminus, it cannot easily be repeated when a person or a group is singing without instrumentation. We need to think about repeatability. Can people carry these songs in their hearts?

Are there possible advantages to having an interlude? Certainly. It is a matter of some subtlety. An interlude gives the congregation a chance to take a breath, stand back a bit, and appreciate the words rather than going straight onwards. The sound of the instruments stands alone during the interlude, and the emotional tone of the interlude might complement and heighten what the individual does when he is singing.

As usual, it is not a question of just following a fixed formula. We need to realistically assess the costs and benefits involved.

Repetition

Let us consider the issue of repetition, both lyrically and musically. Repetition can make learning easier. But it can also become boring. If people are beginning to feel bored, it may make engagement more difficult. There is a trade-off. Weighing the issues is not so easy.

Consider first the issue of repeating words. Repetition makes it easier to remember, memorize, and meditate on the words—but too much repetition may diminish the song’s content. The same phrase repeated over and over does not make for rich worship. So we have to have a balance.

What about repetition in the music? In general, songs with clear-cut stanzas—two, three, four, or even six stanzas—are easier to learn than songs that have no simple, clear-cut musical repetition. For greatest ease, all the stanzas should be identical in their melody. Variations can be interesting to musicians and to singers alike, but they also make the song more difficult to learn.

A song in stanzas looks like this:

Stanza 1: A B C

Stanza 2: A B C

Stanza 3: A B C

Each stanza has different words, but the same music. In our sample case above, each stanza has music with three distinct smaller pieces: A, B, and C. The musical melody extends over the entire first stanza. Then it is exactly repeated in the remaining stanzas.

Of course, if a song is short enough, there may be only one stanza, and little repetition:

Stanza 1 (all alone): A B C

A song like this is learnable because it is short. Too short, some people might say. One scarcely gets going, and it is over.

In general, leaders should consider choosing songs that have more than two stanzas, so that the music is repeated enough to be memorable.

What should we look for in longer songs? If there is no repetition, the melody of the song just develops in one segment after another: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, interminably. Each piece of the song is new music. It is not so easy to learn.

Another possibility is to compose a song with complex partial repetitions. What I have in mind are cases where there are some instances of musical repetition, but also variation. There may be no clear structure of stanzas at all. Or a refrain seems to come in here and there, but not uniformly after every stanza. Or a refrain is repeated twice or three times at the end. Or there is extra music and words at the end that do not match the pattern of earlier stanzas. Here are some examples.

No stanzas:

A B A C B D E E A D.[2]

With refrain:

Stanza 1: A B C

Stanza 2: A B C

Refrain: D E F

Stanza 3: A B C

Double at the end:

Stanza 1: A B C

Stanza 2: A B C

Stanza 3: A B C

Interlude (no words)

Refrain: D E F

Stanza 4: A B C

Refrain: D E F

Refrain: D E F

A congregation can easily follow this kind of arrangement if the leaders provide them with words to read. But the people cannot so easily make the arrangement their own. It is more complicated. Yes, there can be a chorus that is the same for every stanza. Some of the words in the first stanza might be repeated in the final stanza (which would still have the same melody as all the other stanzas). But more complex forms of partial musical repetition cannot be easily remembered.

Once again, we should recognize that there is a trade-off. Repeating the exact same music for three or four stanzas is easier, but can also be less interesting. Variations may help to keep people's attention.

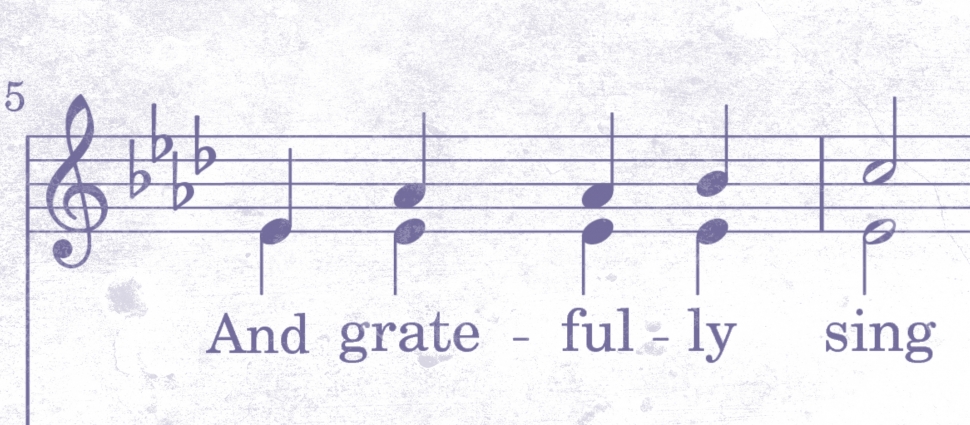

The tune needs to have some repetition, so that it is easy to learn, and some variation, so that it is not unbearably repetitious. For example, some Christian songs have stanzas that begin with two lines with the exact same melody; then a third line with a different (but somehow distantly related) melody; then a final line with the same or nearly the same melody as the first line. This kind of song is such that it is comparatively easy to learn to sing the melody.

The melody should not be boring. There are some Christian songs that may have good words and express good thoughts, but they stay far too much on one note. Or they vary only slightly in a range of about three notes. Just recently I participated in a worship service where one of the songs began with something like six or eight repetitions of the same note. That seemed to me to be too much. The composer may have had some good purpose in mind. But I suspect that most people will find such a beginning too monotonous.

On the other hand, as a rule of thumb a song should not have too much complexity in the melody. The melody should not repeatedly be unpredictable to someone who is trying to learn. Overall, the tune must be somewhere in the middle. Not too complex, because it will be hard to learn. Not too simple, because then it quickly becomes boring.

The melody should be easy to hear. That means that it should be the highest part (typically soprano) and should be loud enough so that it is clearly heard against the background of other simultaneous notes. Why? So that the people can easily learn the melody if they do not already know it. (A male lead voice may work acceptably, but only if he is singing the melody an octave lower and his voice is loud enough to be heard against the background of other notes.)

It is also important that people be able to hear the words. The instrumental accompaniment must not be so loud that it drowns out the words, or so obtrusive that it detracts from attention to the words. Why? Because congregational singing should be a form of teaching, and that involves hearing the message of the words.

The vocal range of the melody should also contribute to singability. The highest notes should not be so high that only sopranos can reach them. The lowest notes should not be so low that sopranos struggle to reach the lowest notes. This issue can come up with older songs in printed hymnbooks as well as newer songs in sheet music. Songs composed in a key that is too high may be transposed into a lower key for the sake of singability.

The music should have clear pause points where people can take a breath. And of course, the distance between pauses should not be so great that the average person runs out of breath too soon.

Now, all of these points are just my opinion. Others may disagree. But I want to encourage people to have reasons to disagree. None of us should merely go with personal preferences, but think about long-term usability by a whole congregation. I want leaders, in particular, to assess whether the music and the arrangement in stanzas make the song easy to memorize. That is one factor to consider. (I say more on memorability below.)

Qualities That Help Accompanists

Composers and music arrangers must also consider the limited skills of instrumental accompanists. Congregational singing takes place in a great variety of settings. Smaller congregations may not have as many trained musicians. A small group Bible study may have only one person who can play an instrument. Ideally, the music should not be difficult for a less skilled accompanist. A key signature of four sharps or five flats is not as easy for a mediocre pianist as is a key of C major or one or two flats or sharps. Multiplying accidentals increases the difficulty.

It is easy for composers to neglect this aspect, because they are much more highly trained. They experience no difficulty. But the constraints of congregational singing make it important for them to lower their sights and make things comparatively easy for people with limited skill.

There is also value in providing music, and not just words, for the benefit of people in the congregation who have some ability to read music.

Memorability

Let us now consider the issue of memorability. The goal in congregational singing should not merely be the narrow one of presenting biblical truth once, by singing a song once. A single instance of singing does help. But one of the advantages of singing is that it reinforces memory.

As we observed earlier, the Apostles sang "a hymn" before they went out (Matt. 26:30). In this verse in Matthew, a "hymn" means a song of praise to God. We do not know what was the musical style. The Bible does not prescribe any one particular musical style. The point is that they sang a song together. They did not have a stack of hymnbooks to pass around. They did not have sheet music. They did not have an overhead screen where the words were projected. So far as we know, they did not have an accompanying instrument. So how did they do it? They all knew the song by heart, and they knew the words. If and when they were thrown into prison, they could sing religious songs for encouragement: "About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them" (Acts 16:25).

How well are we doing, by comparison? Are we training our congregations today so that they could sing Christian songs by heart if they were thrown in prison? What if they are confined to a hospital bed for some days? Or what will our members do if they grow old and lose their eyesight? The saints of previous generations whose eyesight failed could sing the songs they learned and remembered, often from the days of their youth. In the times ahead, will saints with failing eyesight be able to sing from memory?

How well are we doing in preparing people for times of despair and isolation? Can they sing if they fall into despair or isolation in the middle of the week?

I suggest that congregations need to have some common core of songs that they sing often enough so that they stick in the memory—for weeks, for years. If we are flexible, there is room for introducing new songs. But we also need a stable core.

My wife and I grew up in churches in different parts of the United States. But we found when we got married that we knew many of the same Christian songs. Those songs are sometimes still sung in the home church that we now attend. Some of them were sung in England in the churches that I attended there. Some of them were being sung in Taiwan when we visited there. They are almost all over a hundred years old. They have stood the test of time. We know the tunes by heart. We can frequently remember at least the first stanza, sometimes other stanzas. Even when we do not remember the exact words, knowing the tune helps us to pay attention to the words when we sing. We don't have to stumble around trying to learn a new tune. All of this is an aid to the goal of building up. We are built up by remembering the words and by easily participating in singing the words.

Over twenty years ago, my wife and I regularly attended a congregation that predominantly used newer Christian songs. We enjoyed the participation at the time. But we can hardly remember a single one of these songs. They are all gone. No one we know is singing them today.

One implication here is that we need to have balance. If we have new songs, which may have their own appeal, let us also have familiar songs, which many people already know.

Christian artists also undertake to compose new music for old words, that is, the words of older songs. The words are recognizably the same words as before. Only the tune is different. I appreciate the effort. But I wonder once again about the effect. There is a trade-off. On the one side, there can be a sense of freshness, which may sometimes cause people to pay attention again to old words, and to appropriate the old words more vigorously. But on the other side, people labor to learn a new tune, which may distract them from paying attention to the words.

Of course, a congregation can gradually learn some new music and some new words. All the songs in a traditional hymnbook were once new. We may hope that the best of the new songs—the best adapted to congregational singing—may enrich the people of God for generations and generations. My point is that we should be thinking in terms of generations, and not in terms of constantly having something new set before our congregations.

Confidence and Depth in Singing

Memorability in the words and in the music of a song helps people to sing boldly and confidently and robustly. There is a difference when an individual and a congregation participate in singing music with which they are already familiar. Each person can participate more boldly because he is not afraid of making a mistake. Each person can sense, "This is my song." And he can think to himself with the rest of the congregation, "This is our song." It is no longer just the leaders' song. The song can be sung more deeply as a result. I have been in situations where a congregation virtually roars out a rousing song that they already know, like "O for a Thousand Tongues" or "Jesus Shall Reign." A leader and instrumental accompaniment are scarcely needed, except to get the people started on the same note and the same beat. The congregation takes charge. It is wonderful.

But this kind of participation is hardly possible unless the song is in stanzas, all of which have an identical melody. Consider even a minimal deviation, which might be to sing the chorus two times at the end, or to sing the final line two or three times at the end of the last stanza. A congregation cannot do that spontaneously; they need direction from the leader, or at least the overhead projection.

Yes, an extra concluding line can be a nice "wrap-up" to a moving song. That is an advantage. But it is out of the congregation's hands. It is no longer their song, but the leader's song. There is a trade-off here. Yes, there may be a gain achieved by a more emphatic "wrap-up" at the end. But something is lost even by as small a change as one extra line at the end. Larger deviations, such as musical interludes, differences in the structure of the final stanza, or adding new words to the old at the end of each stanza, have an even greater effect. There may be an element of gain, but let us not overlook the loss. The extra elements take the song away from the congregation and make it the leader's song, to which the congregation must passively adjust as well as they can.

We should allow flexibility. But, for the main pattern, the music needs to support the congregation, not the congregation the music. Primarily, the musicians need to accompany the singing, not lead it. But how does this look in practice? That we will consider in our final post.

Vern S. Poythress is Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Biblical Interpretation, and Systematic Theology at Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he has taught for 45 years.

Related Links

Podcast: "What Happens When We Worship"

"A Shallow View of Singing" by Josh Irby

"A Hymn That Would Not Be Written Today" by Gabriel Fluhrer

Pleasing God in Our Worship by Robert Godfrey

What Happens When We Worship by Jonathan Landry Cruse

Reformation Worship Conference: Anthology

Notes

[1] I have noticed that there are interludes or transitions that have a clear musical terminus, and the terminus helps people to know when to come in. But I have participated in other instances where I do not know when to come in as a member of the congregation.

[2] Note that there is some musical repetition, such as the three repetitions of pattern A, but not in an easily predictable order.