On Plundering the Egyptians

The debates surrounding catholicity and theological retrieval do not seem to be slowing down any time soon. With all the back and forth about Thomas, Aristotle, and Van Til, one theological topic seems to be overlooked more often than others—namely, common grace.

Often, the discussion of common grace is relegated to subjects such as marriage, art, government, and science. We think about these as goods not only for Christians, but for all mankind, perhaps recalling that God causes rain to fall on the just and unjust alike (Matt. 5:45). Yet we find common grace at work not only in the actions of unbelievers, but also in their intellect and inner life.

Although clearly different than special grace for the elect, common grace remains a sovereign operation of the Holy Spirit. As John Murray has said, in common grace the Spirit

“…endows men with gifts, talents, and aptitudes; he stimulates them with interest and purpose to the practice of virtues, the pursuance of worthy tasks, and the cultivation of arts and sciences that occupy time, activity and energy of men and that make for the benefit and civilization of the human race.”[1]

Therefore, unbelievers can, by virtue of common grace, come to philosophical conclusions that are helpful and true and can be utilized by the Christian.

This in and of itself is not highly controversial. Though in recent days, when it comes to Aristotle (and Aquinas’s use of Aristotle), there are some who are quick to sound an alarm, typically seeking to eschew these men in favor of claiming “sola scriptura.” This is not, however, how the Reformed have traditionally handled these matters. Rather, Reformed theologians have sought to utilize the insights, metaphysics, and philosophical truths from pagans where it is appropriate, while rejecting that which is antithetical to divine truth. Simply put, the Reformed can affirm the maxim that all truth is indeed God’s truth.

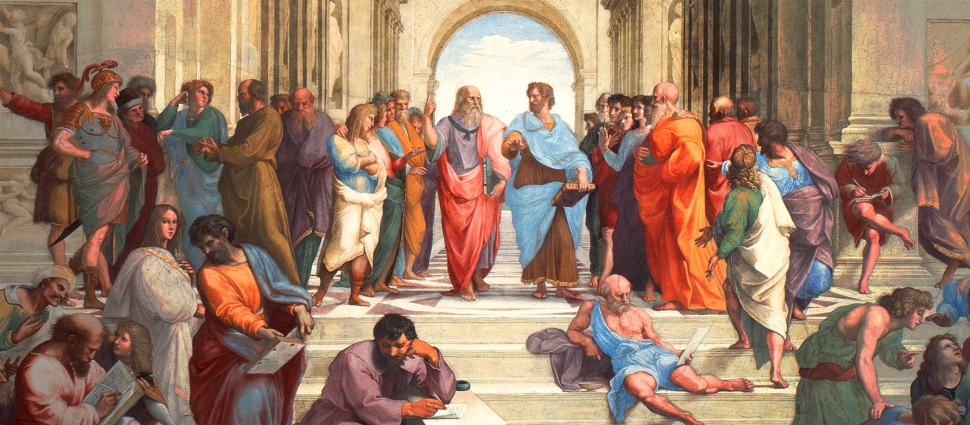

This does not mean that we should uncritically swallow everything that pagan philosophy has to say. Rather, we can claim that which is true as a gift of God, since the Holy Spirit is the fountain of all truth who guides us into all truth (Jn. 16:13). Understanding this allows us to understand philosophy rightly—even that of Aristotle or Plato—and utilize it as the handmaiden of theology. Truth is truth, even if the one who speaks it stands on a faulty foundation.

The Apostle Paul himself is able to freely quote non-Christian sources in favor of his argument. One example is in Titus 1:12, as he quotes “a prophet of their own,” and then affirms the statement in the next verse with “this witness is true.” Commenting on this verse, John Calvin says those who fail to appropriate truth from heathens are superstitious:

“From this passage we may infer that those persons are superstitious, who do not venture to borrow anything from heathen authors. All truth is from God; and consequently, if wicked men have said anything that is true and just, we ought not to reject it; for it has come from God. Besides, all things are of God; and, therefore, why should it not be lawful to dedicate to his glory everything that can properly be employed for such a purpose? But on this subject the reader may consult Basil’s discourse πρὸς τοὺς νέους, ὅπως ἂν ἐξ ἑλλ. κ. τ. λ.”[2]

Notice that Calvin points readers to Basil’s work, which commends young men to learn from pagan writings on virtue. And Calvin is not alone in this. Herman Bavinck in an essay on common grace says:

“The good philosophical thoughts and ethical precepts found scattered through the pagan world receive in Christ their unity and center. They stand for the desire which in Christ finds its satisfaction; they represent the question to which Christ gives the answer; they are the idea of which Christ furnishes the reality. The pagan world, especially in its philosophy, is a pedagogy unto Christ; Aristotle, like John the Baptist, is the forerunner of Christ. It behooves the Christians to enrich their temple with the vessels of the Egyptians and to adorn the crown of Christ, their king, with the pearls brought up from the sea of paganism.”[3]

I dare say that the language utilized by Bavinck in calling Aristotle a forerunner of Christ or Christians enriching their temple with the vessels of Egyptians would make many in modern Reformed circles nervous. But this shouldn’t be the case. Christians are called and enabled to plunder Egypt and take their treasures for the sake of the Kingdom.

It what may surprise some, Cornelius Van Til also affirmed this idea. In Survey of Christian Epistemology, Van Til writes:

“It should be carefully noted that our criticism of this procedure does not imply that we hold it to be wrong for the Christian church to make formal use of the categories of thought discovered by Aristotle or any other thinker. On the contrary, we believe that in the Providence of God, Aristotle was raised up of God so that he might serve the church of God by laying at its feet the measures of his brilliant intellect.”[4]

Although we must use discernment when using pagan philosophies, there is no need to fear their usage in the Christian church. Being able to rightly appropriate these things in service to Christian doctrine is evidence of the Holy Spirit working in common grace and the obligation of Christian theologians. This is precisely what theologians in the Great Tradition in the church sought to do.

We must not fall prey to Socinian or Biblicist methods of theologizing. Rather, let’s follow in the footsteps of those who faithfully proclaimed biblical truth before us, making use of philosophical categories in service to Christ.

Derrick Brite serves as pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Aliceville, Alabama. He received his MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary in Atlanta and is currently pursuing a PhD in systematic theology at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Related Links

Podcast: "What Hath Athens to Do With Jerusalem?"

"Common Grace" by Mark Johnston

"Van Til's Limiting Concept" by Amy Mantravadi

"Reasons for Faith: Philosophy in the Service of Theology," reviewed by Paul Helm

Theoretical-Practical Theology, vol. 1, by Petrus van Mastricht

Notes

[1] John Murray, “Common Grace,” in Collected Writings of John Murray, Vol. 2: Systematic Theology (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1977), 102.

[2] John Calvin and William Pringle, Commentaries on the Epistles to Timothy, Titus, and Philemon (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 300–301.

[3] Herman Bavinck, “Calvin and Common Grace,” in The Princeton Theological Review. Available online at: https://reformationaldl.org/calvin-and-common-grace-herman-bavinck/

[4] Cornelius Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology (Philipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1969).