Doddridge and Evangelical Dissent

Robert Strivens, Philip Doddridge and the Shaping of Evangelical Dissent, Ashgate Studies in Evangelicalism (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015). 201pp. Hardcover.

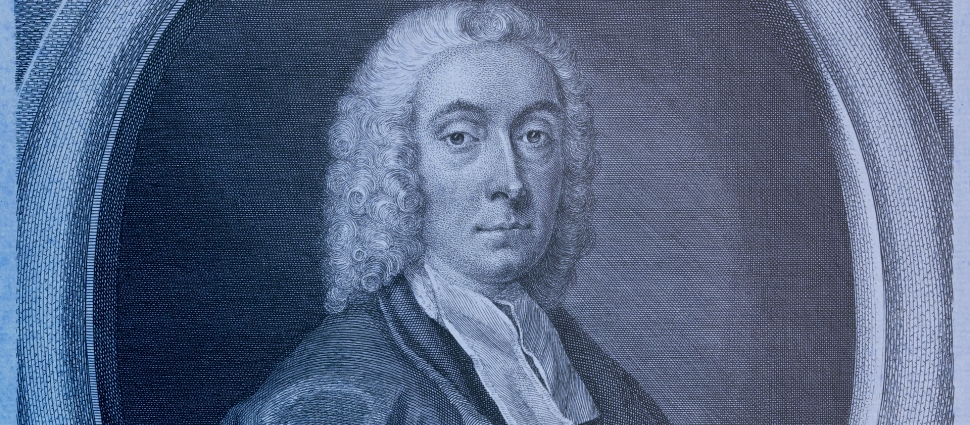

For many students of Reformed Orthodoxy (1560-1790), the eighteenth century “high orthodox” period is notoriously difficult to navigate. The scholastic method, coupled with the use of Aristotelian categories, were gradually eroding. As new methods of logic, organization, and theological goals arose, great diversity arose with it. This resulted in an explosion of theological and methodological differences. While many of these developments were rooted in seventeenth century debates, they came to their own in a new century, with widely differing results in diverse contexts. Robert Strivens’ work on the theology and philosophy of Philip Doddridge (1702–1751) invites readers to begin understanding a portion of these developments in a way that helps paint one segment of a craggy theological landscape. And Strivens does so with well-researched skill and admirable brevity.

In this thorough treatment, Strivens aims to provide readers with a fuller analysis of Doddridge’s theology and philosophy in its historical context than previous research has acheived. He does so in seven chapters, treating Doddridge’s relation to Richard Baxter and “moderate Calvinism,” subscription to creeds and their relation to the doctrines of Scripture and of the Trinity, critical appropriations and modifications of John Locke, shifting views of natural theology as well as natural revelation and reason, his aim and method in preaching, Christian spirituality in relation to Puritanism and cotemporary precedents, and the circle of influences and correspondents surrounding his ministry.

Strivens argues that Doddridge was a “moderate Calvinist,” who drew from Baxter’s spirituality and English Hypothetical Universalism, but who affirmed a Reformed view of Christ’s substitution, justification, original sin, and related issues. Doddridge’s adoption and modifications of the philosophy of John Locke contributed to a shift in education away from Aristolelianism and a rejection of many theological categories that were formerly acceptable. This had consequences, such as a partly ambiguous affirmation of the doctrine of the Trinity, which this reviewer revisits below.

While he imbibed the shift in favor of showing that Christianity was not contrary to reason through the use of natural theology, Strivens argues that Doddridge still affirmed the necessity of biblical revelation for salvation. In relation to such issues, Doddridge aimed to formulate his theology in a way that aimed at simplicity in preaching, pressing sinners to personal conversion to Christ. While his group of friends and influences included heterodox figures, such as Samuel Clarke and Isaac Watts, he aimed to include among the orthodox a broad range of evangelical and “high orthodox” ministers. This paints a well-rounded picture of Doddridge as a complex figure who illustrates the persistence of older Reformed theology in some ways and exemplifies its transformation in others.

A few features of this analysis stood out to this reader as particularly noteworthy. In particular, his chapter treating Doddridge’s view of creeds and confessions and the doctrine of the Trinity sheds light on some thorny issues. Doddridge rejected subscription to “any set of Articles” In 1719, Dissenters in London voted by a small margin not to require confessional subscription in relation to the Trinity in particular (47-48). These men argued for using Scripture language only and thought that subscription to creeds hindered unity. In this context, Doddridge advocated people writing their own confessions for ordination (49). Many today continue to debate the nature of subscription to creeds. However, the purpose of creeds and confessions has always been partly to serve as a standard of unity for ministers by assuring that all ministers in a church confess and teach the same things. It is difficult to see how a church can achieve this without establishing agreed upon summaries of doctrine over which all are agreed, rather than each candidate inventing his own creed upon ordination. The absence of creeds runs the risk of detaching the church from believers in all ages and making the standard of unity a moving goal line.

Strivens’ treatment of Doddridge on the Trinity also clarifies important issues. Doddridge’s views on the Trinity were suspect in relation to Christ’s pre-existent nature, the relations within the Godhead, and his attitude toward those who held heterodox views (59). He believed that Christ had a pre-existent and changeable nature in addition to a divine nature. This created nature was necessary, in his view, to justify Christ’s incarnation without detracting from divine immutability. Watts taught this as well, adding that this nature was in fact human, which Doddridge rejected. While neither Watts nor Doddridge followed him on this point, Samuel Clarke taught the eternal subordination of the Son to the Father. The relevant issue here is that Doddridge treated all of these views as acceptable. This was a consequence both of his attitude towards confessions and his rejection of scholastic terminology, which is necessary to maintain unity in relation to historic trinitarian doctrine. This material can potentially provide insight into contemporary trinitarian debates that suffer from similar dilemmas.

While this study is thoroughly researched and helpful, there are a few areas in which it would be clearer in light of further interaction with seventeenth century thought. For example, Strivens does not show adequately the shift in Reformed attributes towards natural theology and natural law at the dawn of the Enlightenment, and the diversity that increasingly existed among Reformed authors at this point (83). Engaging with wider scholarship on seventeenth century controversies on such matters would provide a fuller trajectory of the nature of seventeenth century developments.

The eighteenth century faced many changes. This means that studying theological developments in this time period can be a difficult task. Strivens fills in part of the English context through his careful study of Philip Doddridge. This material is useful historically and it has potential to bear fruit in ongoing theological discussions over key issues.

Ryan McGraw (@RyanMMcGraw1) is associate professor of Systematic Theology at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Greenville, South Carolina.

Related Links

"Book Review: Introduction to Scholastic Theology" by Ryan McGraw

"Van Mastricht on the Scholastics" by Nick Batzig

All That Is in God by James Dolezal

Theoretical-Practical Theology, vol 1, by Petrus van Mastricht

David's Son and David's Lord, edited by Ryan McGraw and Michael Morales

Note: This review appeared in Mid America Journal of Theology, vol. 28, 229-231.