Defining Definitive Sanctification

Is it possible to “get saved” without getting sanctified? The 1689 Confession, in accordance with the Bible, answers with a resounding “No!” Sanctification is not an optional extra for Christians; it is an essential part of the salvation God gives to all who are in union with his Son. Every Christian is sanctified.

When does this sanctification start? Consider again the opening clause of the LBCF 13.1:

“They who are united to Christ, effectually called, and regenerated, having a new heart and a new spirit created in them through the virtue of Christ’s death and resurrection are also farther sanctified... .”

It is evident that this description is intended to describe the beginning of sanctification, because the confession states that the Christians in view are “farther sanctified,” which presupposes an initialsanctification. Here we see that there is the inception of sanctification, and then there is the increase of sanctification.[1] According to the confession, our union with Christ in His death and resurrection has not only secured our justification, but it is the basis and the effectual cause of there being created within us a new heart and a new spirit.

This is initial sanctification, which may also be called “definitive sanctification.”[2] There is a definitive sanctification at conversion, followed by progressive sanctification throughout the course of the Christian’s life.

By “definitive,” theologians mean a decisive, once-and-for-all act. When we speak of sanctification, generally we tend to think of it as a gradual process of moral and spiritual transformation.[3] It is right and biblical to apply the term “sanctification” to this process.[4] But it is often overlooked that in the New Testament sanctification is not only spoken of as a process. It is also often spoken of as a decisive act.[5]

The term “definitive sanctification” is a way of referring to the “basic and radical change that takes place in a sinner’s moral and ethical condition when he is united to Christ in effectual calling and regeneration.”[6] At the moment of his conversion, the sinner is certainly justified, pardoned and accepted by God on the basis of the merit of Christ put to his account. Yet that is not all that happens. In the same moment, there is also a decisive separation from the reigning dominion of sin, as well as a consecration to God. This is more than theological hair-splitting; it is glorious news proclaimed from the pages of Holy Scripture.

* * *

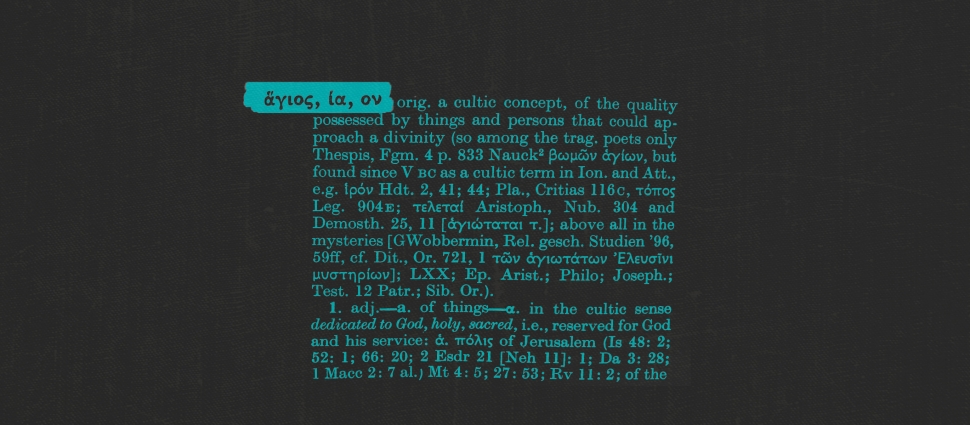

In terms of frequency, the word for “sanctification” in its adjective, verb, and noun forms is used more often to refer to definitive sanctification than it is to progressive sanctification. First, there’s the adjective form which is translated, “holy,” or “saint” (hagios, ἁγίος). It is often used in the plural to refer to all Christians, not just to a select few. All believers are referred to in the New Testament as “saints,” or “holy ones,” or “sanctified ones.” For example, Paul addresses his epistle to the Philippians, “To all the saints in Christ Jesus which are at Philippi.” “To all the saints,” literally, “to all the holy ones, the sanctified ones.” This implies that at conversion every believer is made a holy one, a saint. There has been a definitive separation from common use and separation unto devotion to God.

Second, we often see the same thing in the way the verb form of the word is used. For example, consider 1 Corinthians 1:2: Paul is introducing his letter and writes, “To the church of God which is at Corinth, to those who are sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints.” Notice, he refers to these Corinthian Christians as “those who are sanctified.” We have here a participle in the perfect tense, which could be translated as “those having been sanctified,” or, “those who have been sanctified,” or simply, “sanctified.” This is something that has already occurred once and for all. In the New King James translation from which I am quoting, the words, “to be” in the phase, “called to be saints,” are in italics. This translation implies that being a saint is a goal they must attain and that would be true.[7] But in the first part of the verse they are described as already sanctified and this may be the idea in this last phrase as well. This is better captured by the New American Standard translation “saints by calling,” instead of “called to be saints.” They have been sanctified and they are saints.

Consider 1 Corinthians 6:11. Paul is describing what happened to these Corinthian Christians at their conversion and he says, “And such were some of you. But you were washed, but you were sanctified, but you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus and by the Spirit of our God.” Notice two things here. He says, “You were sanctified.” Again, this is a sanctification already true of them. Then notice the order. Which comes first in this verse, sanctification or justification? Sanctification comes first. This is not progressive sanctification that follows justification. This is a definitive sanctification. They were washed, through the washing of regeneration, by virtue of which they were sanctified. They were set apart from sin unto God and unto holiness. And they were also justified, declared righteous in their legal standing on the ground of the righteousness of Christ put to their account. All of this had already occurred at their conversion. They weren’t being washed, being sanctified, and being justified, they were already washed, sanctified, and justified.

Third, we also often see this in the way the noun form of the word is used. Consider 2 Thessalonians 2:13, “But we are bound to give thanks to God always for you, brethren beloved by the Lord, because God chose you for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in the truth.” Notice the order, “Sanctification by the Spirit and belief in the truth.” Sanctification is mentioned first. Then notice something else important here. This sanctification is an operation of the Spirit. It is not simply a change in legal status or a change of position. This is the way that some have interpreted these texts we have been surveying. They agree that these texts are not speaking of the ongoing progressive sanctification of the believer, but then they say that they are speaking of a positional sanctification that occurs at conversion.[8] But here in 2 Thessalonians 2:13, Paul is not speaking merely of a positional change, a mere change in legal status or position before God. This initial sanctification is a work of the Spirit. It is a subjective change in the person, and of the person, produced by the Holy Spirit. This is why the term “definitive sanctification,” as opposed to “positional sanctification,” is much better for describing this initial aspect of sanctification. Now there may, indeed, be a sense in which we can describe this initial sanctification as positional. It does involve a change in our position, in the sense that we are now set apart unto God. But it is not only a positional change. It is a real and subjective change. As the confession states, it involves “having a new heart and a new spirit created in them.”

Consider 1 Peter 1:2. Peter is introducing his letter and he describes those to whom he is writing as, “elect according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, in sanctification of the Spirit, for obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ.” Peter references the entire Trinity. We have election according to the foreknowledge of God the Father. We have sanctification of the Spirit. And we have sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ. Notice the order. This is not a progressive sanctification that follows conversion. This is an initial sanctification that occurs at conversion. Here we have the word “sanctification” followed by the preposition eis with the accusative, meaning “into,” “unto,” or “with this goal or intention,” and you’ll notice again that this is a work of the Spirit. This is not merely a positional sanctification, just a change in status, like justification is. It is a work of the Spirit issuing in obedience.

All of these uses of the word in its adjective, verb, and noun forms force us to the conclusion that sanctification is not to be thought of exclusively in terms of a progressive work. Sanctification in one sense is to be thought of as a progressive work, as we will see later. But in these texts, the language of sanctification refers to a decisive action or event that occurs at the very inception of the Christian life and one that characterizes all true believers.

We can see the definitive aspect of sanctification in the way the word is often used in the NT. But we can also push a bit further by exploring how the New Testament describes what happens in conversion. We will turn our attention to this in our next post.

Editor's Note: This post has been adapted from A New Exposition of the London Baptist Confession of Faith of 1689, edited by Rob Ventura, slated for release by Mentor Books in November 2022.

Jeffery Smith has been in pastoral ministry since 1990 and since 2009 has been serving at Emmanuel Baptist Church, Coconut Creek, FL. In addition to his regular pastoral and preaching responsibilities, Jeff serves on the governing board and as a lecturer for Reformed Baptist Seminary. He is the author of: The Plain Truth About Life After Death (Evangelical Press, 2019) and Preaching for Conversions (Free Grace Press, 2019).

Related Links

Podcast: "I Feel the Need..."

"The Cross-Bearing Life" by Mike Myers

Holiness; Its Nature, Hindrances, Difficulties, and Roots by J. C. Ryle

PCRT '19: Redemption Accomplished and Applied, with D.A. Carson, Kevin DeYoung, Richard Phillips, and more.

The Need for Creeds Today by J. V. Fesko

The Creedal Imperative by Carl Trueman

Notes

[1] Sam Waldron uses this language of “inception” and “increase” in his outline of this chapter in A Modern Exposition of the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith (Darlington, Co. Durham, UK: Evangelical Press, 1989), 174.

[2] I believe this language “definitive” sanctification was first used by John Murray or that it was at least popularized in modern reformed theology by his use of this term to describe the inception of sanctification. See John Murray, Collected Writings of John Murray, Volume Two: Select Lectures in Systematic Theology (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1977), 277-284.

[3] Ibid. 277

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Waldron. Modern Exposition of the 1689, 175.

[7] David E. Garland, 1 Corinthians: Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2003), 27.

[8] Michael P.V. Barret, Complete in Him: A Guide to Understanding and Enjoying the Gospel (Greenville, SC: Ambassador-Emerald International, 2000), 196-97. Dr. Barret writes, speaking of this first dimension of sanctification, “it refers to positional sanctification. This is most likely the sense intended by Paul when he identified the believers in Corinth “as sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints”…The whole point of the epistle is that in practice, the Corinthians were not acting like saints (literally, holy or sanctified ones), although in reality and fact they were saints. This positional sanctification essentially equates with justification and designates the acceptance the believer has before God in Jesus Christ.”